Understanding purposes meta-rationally

A collaborative improvisational dance of the participants and paraphernalia in a context, continually revealing new opportunities and obstacles.

This is a draft chunk from my meta-rationality book. If you are newly arrived, check the outline to get oriented. (You might want to begin at the beginning, instead of here!) If you run into unfamiliar terms, consult the Glossary.

This post may seem overly abstract unless you have read the previous one, about purpose in software development. Keep that material in mind while reading this post, to make it concrete. Everything here has direct applications in “software requirements analysis.” The following post explains that explicitly. It won’t make sense unless you have read this; and this one may not make sense unless you have read the previous post!

It may be easiest to understand the meta-rational approach to purposes by contrasting it with their roles in reasonableness and rationality.

This summary table provides an overview:

You may already get a sense of where we’re heading by going through the table now. You may also want to refer back to it repeatedly as you read on.

Purposes are the currency of reasonableness

Accountability is the essence of reasonable thought and action. Accounts answer the question “is that reasonable?” with reference to a purpose. Here are the examples I used in the chapter on accountability in Part Two:

I should get a haircut. It’s overdue

You didn’t turn the oven off—no wonder the cookies are so hard

He went to the post office to see if the check had arrived

Why is Yvonne going on a date with that Harold guy?

An account explains how what you did conformed to relevant social norms. Those norms are usually tacit or at least vague, and their applicability depends on unenumerable features of the immediate situation; so they are always negotiable. That negotiation is “groundless”: it can never reach a bedrock of unassailable compulsion.

Reasonableness is concerned mainly with immediate, local opportunities in routine activity, so reasonable purposes are generally only operative briefly. When you aren’t in a situation in which a purpose is relevant, it vanishes.

Reasonableness implies purposes must mainly conform to “what one does in that sort of situation,” so it’s mostly best to think of them as held by the local social group rather than an individual. It’s difficult to maintain unusual long-term purposes when in this communal mode; those are unreasonable.

Rationalist theories of purpose are metaphysical and unrealistic

We saw in Part Three that ignoring considerations of purpose is why rationality works. The Solution to a formal Problem is either correct or incorrect, regardless of what purpose the Solution may later be put to. The same valid Solution to “devise a more potent acetylcholinesterase inhibitor” may be valuable as an agricultural pesticide or as a chemical warfare agent.

Education for rational professions specifically teaches you how to ignore questions of purpose. In almost all cases, it specifically avoids teaching you ways of considering them. Universities, if embarrassed by this, may require you to take a few “humanities courses” that pretend to. In most cases, it is unlikely you will learn from them anything about purpose of practical value.

Where do Problems come from? That is not a rational question. In university, the professor assigns “problem sets.” Why those problems? That’s not for the student to ask. In employment, an ideal rational worker gets Problems in their inbox, uses rational methods to Solve the top one, puts the Solution in their outbox, and goes on to the next Problem. Those may be literal boxes full of paper, or nowadays it’s more likely a software task management system. Implicitly, then, for rationality to operate at all, some external authority must create Problems whose Solutions further its purposes.

Like most of my posts, this one is free. I do paywall some as a reminder that I deeply appreciate paying subscribers—some new each week—for your encouragement and support. It’s changed my writing from a surprisingly expensive hobby into a surprisingly remunerative hobby (but not yet a real income).

That’s fine for rationality. It’s unsatisfactory for rationalism, which is vaguely aware that a rational theory of rationality would need to specify the source of Problems. Abstract objects in the metaphysical realm are the substance of a rational theory, so the purposes from which Problems derive must live there. Purposes must, then, be propositions; and Problem derivation must proceed by formal inference. The paradigm—the example to emulate—must be Euclid’s Elements, in which all truths of geometry derive from a handful of incontrovertible axioms.

So rationalist theories of purpose posit some fixed, ultimate, abstract, context-free purpose. That might be maximizing utility, or a set of “values” or “terminal goals” or “categorical imperatives.” As with propositions in general, axioms of purpose are imagined to be perfectly definite, although they can’t actually be specified definitely. (Nobody can explain specifically what “utility” is.)

As with rationalism in general, the ontological nebulosity of purpose gets misinterpreted as epistemological uncertainty. That implies there is an ultimate purpose, because there must be one, or else the theory wouldn’t work. We just don’t know exactly what it is. The rational Problem-creating agent, then, would be an individual mind with an imperfect view into the metaphysical realm of abstract propositions.

On the rationalist view, a specific Problem should be derived logically from the ultimate purpose plus facts about the current state of the world. You might use game theory, decision theory , control theory, or means-ends planning, as discussed in “Acting on the truth” in Part One. All these are ways of setting up formal Problems, so once you have ascertained the ultimate purpose, you should proceed entirely rationally, with no need for either meta-rationality or reasonableness. Determining your immediate purpose, what you should be doing right now, is itself just another Problem.

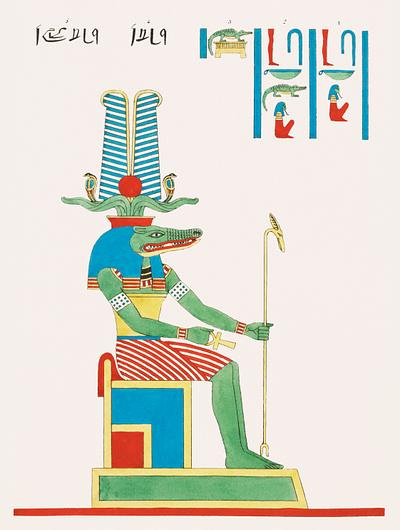

Your ultimate purpose (you have somehow determined) is to please Offler, the Crocodile God. Offler delights in the smell of sausages frying. Therefore, you derive a more specific purpose of maximizing sausage odor, which He can sense anywhere in the universe, being omnipresent. Sausages cost money, so you have a purpose of making as much as possible. Years ago, you logically determined that, considering alternatives, you can maximize your income by trading pork belly futures. Because you are extremely rational, you are extremely good at this, have come to control a substantial fraction of the entire pork belly market, and donate almost all the profits to the Crocodile Temple, which uses them to buy and fry boxcar loads of sausages. To maximize sausage scent, of course you eat exclusively sausages yourself. Your doctor has told you that this has clogged your blood vessels and you will die imminently. You reason that, as a major Temple donor, it is important for you to live as long as possible—another derived purpose. Therefore, to counteract the sausages, you have taken up running. Right now you are putting on your running shoes, which you have logically determined is necessary to support your purpose of running. Your right shoe is on, and you are tying the left one. You’ve got one lace end in your right hand, and reason that, in view of this chain of derived purposes, your next action must be to grasp the other lace end with your left hand. In order to please Offler, the Crocodile God.

Unfortunately, as “Acting on the truth” explained, reasoning rationally about what to do doesn’t work, except in highly restricted situations. (Those are mostly ones that that have been engineered meta-rationally to make a specific rational method reliable.)

Tacitly or explicitly, rational people recognize that rationalist theories of purpose generally produce bad results, so we are reluctant to apply them. Rationalism—the delusion that you should always use rationality for everything—disapproves. Under the sway of rationalism, some unfortunate souls attempt to determine their life purpose rationally, which always fails. Pursued seriously, this typically results in post-rationalist nihilism, when you realize that you can’t justify your existence by reasoning from first principles.

Lacking a rational explanation of broad purposes, merely rational people are reluctant to consider them in their work at all. Education for rational professions does not teach tools for that, and rational workers don’t feel qualified. “That’s above my pay grade.” The hope is that the external authority supplying Problems (your boss, maybe) has some better understanding of what the right purposes are. Then you can feel good about just taking a Problem out of your inbox, Solving it, and sending that on to whoever or whatever will use your results—for some purpose you'd rather not speculate about.

The authority may have a better idea; or they may not. Refusing to take personal responsibility for evaluating purposes—which requires meta-rationality—may have bad consequences for you personally, and/or for the people your Solutions are imposed on. More on that in a future post.

Meta-rationality understands purposes as interactions in context

Recall from the very beginning of Part Four:

The essence of meta-rationality is actually caring for the concrete situation, including all its context, complexity, and nebulosity, with its purposes, participants, and paraphernalia.

For meta-rationality, purpose is an unrolling dynamic, a collaborative improvisational dance of the participants and paraphernalia in a context, continually revealing new opportunities and obstacles. Meta-rationality requires letting go of rationalist promises of certainty, understanding, and control, in favor of appreciating the inseparability of the nebulosity and patterns of purposes.

Purposes are clearest as opportunities in routine activity.1 While eating lunch at your desk, you notice you’ve got a bit of blueberry jam on your keyboard, and reach for a kleenex to mop it off. Unambiguously and certainly, your purpose was to remove the jam. However, you may have done that with little or no thought, and immediately forgotten about it—as is typical in routine activity. So the clearest examples of purpose are easily overlooked when theorizing action.

Purposes, desires, values, plans, goals, intentions: their primary manifestations are as aspects of activity in concrete situations. Your armchair beliefs about them are vague memories of what you felt and did in the moment, not the things themselves. Explicit representations of purposes—verbal statements, written plans—are derivative phenomena. Most purposes are tiny and momentary and may never be represented by anyone.

How to invent kleenex

We abstract and generalize from such moments. This is often valuable, as abstraction and generalization often are. The Cellucotton company invented kleenex by observing recurring patterns of face-wiping purposes, and adapted a WWI chemical warfare gas mask filter as a product for removing cosmetics. Customers, when they needed to blow their noses and kleenex was ready to hand, discovered a new purpose. Cellucotton only learned from them that purpose, and started promoting kleenex for it, years after they first introduced the product.

We often find “medium-sized” purposes bottom-up this way, empirically rather than deductively. That always results in some loss of precision, accuracy, and relevance, which contributes to the nebulosity of purpose. The trade-off is often worth making, but meta-rationality recommends remaining aware of it.

Although rationalism’s attempts to deduce purposes top-down from some ultimate goal necessarily fails, larger purposes frequently do justify smaller ones. You probably do need to put shoes on to go running, and probably you need money to live. Meta-rationality recognizes that such reasoning is always fallible, though. Some people run barefoot, and some monks live in monasteries without money. There is no guaranteed way of deriving smaller purposes from larger ones, and no largest, ultimate purpose.

Therefore—contra rationalism—there can be no final or universal grounding or justification for anything. Nevertheless, purposes are often incontrovertible in context, like your purpose in reaching for a kleenex, or the purpose for penicillin. “No ultimate purpose” does not imply nihilism! We’ll come back to that later.

(Around now might be a good time to review the table that contrasts reasonable, rational, and meta-rational approaches to purpose?)

For meta-rationality, purposes are located in the broad context, rather than in accounts of social norms in a narrow situation (as in reasonableness), or in the abstract realm (as in rationality). So, what is “the context”? It includes the immediate concrete situation, but also everything that is relevant to purposeful activity within it. That may include, for example, abstract concepts and knowledge; rational and non-rational methods; and institutions, individual people, objects, and events distant in space and time.

So how do you know who and what are or aren’t included as “participants and paraphernalia?” Relevance can’t be determined rationally, or by any fixed method; so the scope of the context is itself nebulous, and therefore a matter of meta-rational judgement. Reflecting on “do I need to consider that? does it matter for the purposes?” is an always-ongoing aspect of meta-rationality.

Meta-rationality is necessary when the context is a mess. A mess is sufficiently nebulous that reasonableness breaks down. A mess is sufficiently nebulous to constitute a mass of anomalies: phenomena for which rationality isn’t applicable; not without meta-rational aid and guidance.

If you want to apply rationality—not always a good idea—you need some Problems. Problems are formal objects, and therefore not inherent in a mess (or anywhere else in the material world). They are not objective givens, independently existing. They are created through meta-rational consideration of the messy context together with available resources, including relevant rational methods.

How to create Problems, starting from a mess, is the topic of a large upcoming section, so we won’t go into that much here. Instead we’ll observe just that useful Problems are those whose Solutions can serve purposes. So, accurately understanding the purposes in a mess is a prerequisite for sensible application of rationality. Although purposes are inherently nebulous, making them explicit and increasingly precise, sometimes even formal, is necessary in creating Problems.

In a big mess, purposes manifest in complex interactional dynamics, often spanning a large chunk of the context. That may include many people and elaborate systems. You can’t just take a quick look around and locate purposes as distinct objects. You can’t rely on what participants say their purposes are, because in a big mess they have only a local view. Since purposes are interactional, some—often the biggest, most important ones—don’t live in people’s heads as representations.

Understanding purposes in a context must begin with tentative informal observation and exploration. This meta-rational investigation gradually makes the understanding of purposes clearer, more specific, more concrete, more accurate, more relevant both to the concrete situation and technical Solving approaches and resources.

It is tempting to shirk this step. It is common to jump directly to a premature formalization of a superficial, inaccurate understanding. The mess is nebulous, which cues the nausea of groundlessness: how do you know whether you are doing it right? There is no definite method. There are no specific criteria; only your meta-rational judgement, drawing on experience.

Competent mess exploration demands the characteristically meta-rational ability to relate masses of seemingly-trivial concrete details with the nebulous big picture.

Exploring a mess may require sorcery: ignoring boundaries between expertise domains. There is no body of rational professional expertise applicable. You may need to employ many disparate sorts of knowing-that and knowing-how to get a panoramic understanding.

Incrementally formulating your understanding requires continuing awareness that you can never fully characterize a mess. You must bear in mind that you are omitting aspects that may be relevant. Some you deliberately neglect, with a meta-rational judgement that it’s worth the risk. Some are entirely unknown unknowns. Your understanding will always be incomplete and imprecise. You must consider and accept the consequences.

Purposes and Solutions are mutually constraining. A Problem whose Solution satisfies no purpose is not a good or useful Problem. This is often described as “a solution in search of a problem,” although “purpose” would be more accurate than “problem” here.

A purpose that can’t realistically be fulfilled is not actually a purpose, or not a meaningful one anyway. It’s just an idealistic fantasy or wistful longing. (“Realistically” is subject to meta-rational judgement, of course. Are flying cars realistically possible? Not now. Are they worth pursuing? Hard to say.) Useless Problems and unrealistic purposes are both common failure modes in the meta-rational work of Problem creation.

Therefore, understanding purposes in context can’t be separated from a preliminary understanding of how they might be satisfied. When rationality is involved, this implies that Problem creation and purpose identification are intertwined. They must proceed jointly, at least in part. Increasing understanding of each illuminates or invalidates progress in the other.

Purposes don’t hold still. They emerge, evolve, and dissolve in response to contextual shifts: changes in economic and material circumstances, social dynamics, technological innovations, and the psychology of participants. Ideally, your understanding of purposes should track these developments. Recall from “Sorcery”:

Meta-rationality reevaluates a situation more for the sake of allowing the ongoing unfolding of its meanings than for any specific systemic improvement. For meta-rationality, “what does this situation need?” remains a permanently open question, whose meaning shifts fluidly over time. There are no fixed goals; no Problem to be Solved. What counts as improvement, progress, or achievement is nebulous, and develops dynamically.

Purposes usually have ethical implications. They often also have social implications, including for shifting power dynamics. An upcoming post discusses these complexities as part of the work of formulating purposes and Problems.

I would love to hear what you think!

A main reason for posting drafts here is to get suggestions for improvement from interested readers.

I would welcome comments, at any level of detail. What is unclear? What is missing? What seems wrong, or dubious?

The philosophically inclined may, around about now, contemplate demanding a definition for “purposes,” and an explanation of their metaphysical status. What is a purpose, really? This book is aggressively uninterested in philosophical questions. It’s meant to be practical. You already know what “purpose” means, and doing philosophy on the word won’t level up your technical work, which is the purpose of the book.

In this post, Reasonableness, Rationality, and Meta-Rationality line up as descriptions of purpose under:

* Kegan Stage 3: Reasonableness — Purpose under socialized mind

* Kegan Stage 4: Rationality — Purpose under systematic mind

* Kegan Stage 5: Meta-Rationality — Purpose under meta-systematic mind

Exploring Kegan Stage 1 and 2 (and stripping them of some of the negative valence back-cast upon them by higher levels):

* Kegan Stage 2: Wild Desire — Purpose, independent of socialization (socially unaccountable)

* Kegan Stage 1: Impulsivity — The collapse of purpose, problem, and solution into a singularity; purpose arises as a purely bodily event, not distinguishable from action taken to solve the implicit problem.

Quotidian examples in an adult of Wild Desire might be selecting material to watch from the endless choice of the internet when by oneself (especially when it comes to erotic material) or deciding that it is a good moment to start preparing for bed. Unlike impulsivity, there is cognizance of the choice. Unlike reasonableness, there may be no implicit relationship to social norms

Quotidian examples in an adult of Impulsivity range from scratching an itch to spontaneously putting one's hand out a window while driving to feel the wind. A vast majority of adult actions are probably both impulsive and of negligible social consequence; only dramatic examples of impulsive behavior become fodder for further discussion.

This seems so so relevant to me! I tried to apply formal methods for problem, definitions or different frameworks for software development, but they always failed. I thought many people used them and succeeded, so maybe I'm just dumb. Now it seems to me that my desire to use these methods was compulsive avoidance of uncertainty, and not knowing about these methods would be better for me.

Also reading this chapter, I recall reading the book "the dynamic structure of everyday life". I only read several chapters from it, but I plan to return to it. It seemed so interesting to me, this deep exploration of routine activities in order to elicit patterns in them and find ways to create tools to support these activities.

since you know about this book, would you recommend it for better understanding of meta-rationality?