Subcultures: 10/14/88

A dark taste of the subcultural era, written just past its peak

I am rereading my diaries from the late ’80s. That’s background research for writing “Liota,” the second in a series of true1 stories about transformational romantic relationships. (The first was “Elena.”) I’m finding my writing from that era emotionally overwhelming, so I have to take it in small doses. I’m also finding it fascinating as cultural history. Much that I lived through and had forgotten.

Liota was a lesbian feminist sadomasochist Pagan anthropologist.

One of the incomplete projects I most want to return to is the “Subcultures” section of Meaningness and Time. That period—the ’70s through ’90s—was culturally formative for me personally. But it also offers unique resources for resolving current cultural conflicts and cul-de-sacs, as I wrote in “Desiderata for any future mode of meaningness”:

The subcultural mode abandoned universality, in favor of rigorous particularism. Different subcultures provided different bodies of meaning, suitable for different sorts of people. Finding the right subculture let you “be yourself.” Finding the right subsociety gave you a feeling of “coming home to my own people, at last.” This new mode provided a much better—nearly customized—self/society fit than the systematic and countercultural ones could.

Not needing to justify any universal claims, subcultures no longer had a use for any eternal rock of certainty. They maintained coherence thematically, with aesthetic judgements and with ritual, rather than with a foundational structure of justifications. This put them on track toward the complete stance: neither eternalist nor nihilist.

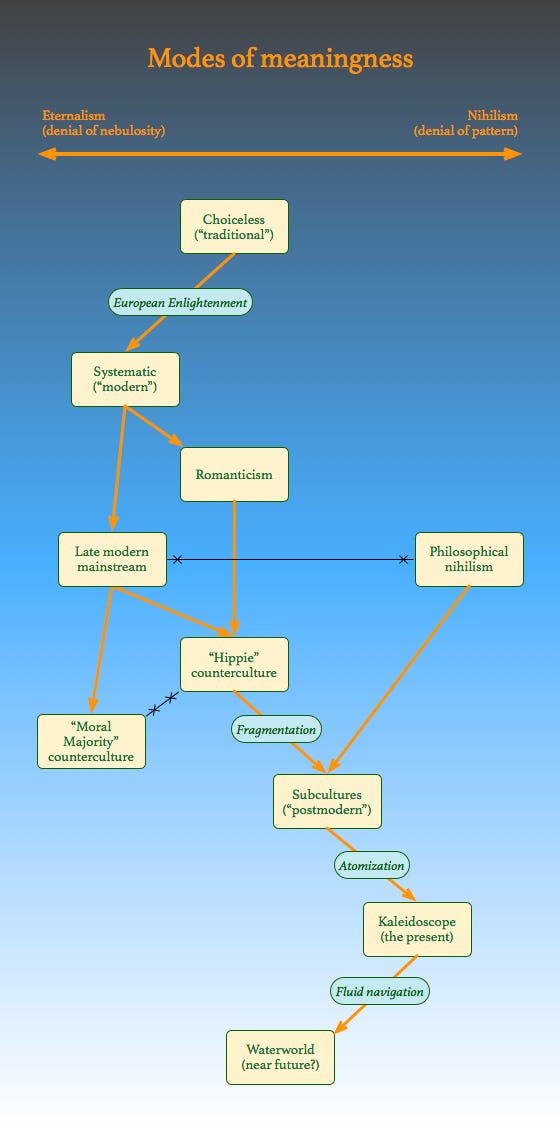

This diagram from “Modes of meaningness, eternalism and nihilism” illustrates the point, and a hope for our future:

Freed from pompous eternalism and dour nihilism, subcultures became explicitly play. Steampunk is deliberately ridiculous, and not meant to be taken seriously. But it is also not trivial genre entertainment, as it may appear to outsiders. The subcultures began to explore the possibility that seriousness and playfulness are not mutually exclusive. That inseparability should be a major, explicit aspect of the fluid mode.

At their best, subcultures were refuges from the screeching chaotic dysfunction of nation-scale systematic social institutions and the nation-scale culture war.

In 1988, the subcultural mode was just beginning to disintegrate. Individual subcultures could not, after all, provide sufficiently complete and dense patterns of meaning for their participants. Internal schisms produced increasingly numerous, increasingly narrow subculturettes. Increasingly, we hopped between them, or attempted to combine several. A few years later, the subcultural era ended, replaced by the atomized era:

The subcultural mode failed because individual subcultures did not provide enough breadth or depth of meaning; and because cliquish subsocieties made it too difficult to access the narrow meaningness they hoarded.

The global internet exploded that. Everything is equally available everywhere—which is fabulous! Now, there are no boundaries, so bits of culture float free. Unfortunately, with no binding contexts, nothing makes sense. Meanings arrive as bite-sized morsels in a jumbled stream, like sushi flowing past on a conveyer belt, or brilliant shards of colored glass in a kaleidoscope.

10/14/88

My diary from this date makes some of the points I wish to restate thirty-seven years later. More cheerfully! I was not having a great time.

The diary entry reads:

Vast slabs of culture-stuff slowly grind across the plain of history. The faults at which they collide are great cultural contradictions, incoherences endlessly papered over and endlessly gaping.

The people caught in these subduction zones we call mad. The cultural construction of insanity provides a symptom vocabulary with which we can express the intolerable pressure at the juncture of these tectonic worldviews.

Subcultures try to provide coherent identities for their members in a world in which the culture at large has become so fragmented that to keep a coherent sense of self together has become very difficult. If I call myself a sadomasochist or clone or skinhead or Jehovah’s Witness or dyke or New Ager, then I know what to wear and what to eat and what music to listen to and what to talk about and how to have sex.

Recently I discovered that Boston has a bisexual sadomasochist support group. I thought this very funny and suggested that I’d have to start a bisexual sadomasochist Pagan support group. But that, it turns out, would be redundant: half of them are Pagan anyway.

I dive into these subculture not hoping to be converted, to “become” these things—I know that is impossible for me—but hoping that they can somehow explain myself to me. They wash over me and I learn a little and jump into another.2 And if all the bisexual sadomasochists are Pagans, this must not be uncommon.

There’s a story about a census-taker working a southwest American Indian reservation. They had big extended families there, so he’d ask some adult who was home to list all the family members and their relationships. Often enough, he’d hear something like “Well, there’s my great-great-grandmother and all four grandparents and six aunts and three uncles and their eighteen children and my wife and our four children and the anthropologist.”3

I am struck by the prevalence of anthropologists. The most intensely eclectically subcultural people I’ve met have often been anthropologists. And I think they are there doing that for the same reason I am.4

For me I suspect this is all in part substitution. If I could have a coherent culture I wouldn’t go off into this darkling underworld. If I could have a Normal American Marriage, I wouldn’t be doing s/m. But it’s much too late for me to have a Normal American Marriage—much too late for most Americans, in fact. We’ve been caught between the grindstones of history, between the Normal American Marriage and feminism and the necessity of two-income families and the availability of reliable contraception and abortion and it’s too late. No one can ever have a coherent relationship again.

That last sentence was much too pessimistic! But the passage is also prophetic. Despite tradwife larping and RETVRN propaganda, a fully Normal American Marriage, of the Authoritarian High Modernist variety, is possible only within tiny, extreme subcultures. However, relatively coherent marriages are still possible. I am glad to say I have one!

-ish.

That’s what I wrote, but I don’t think “they wash over me” was accurate. (I was feeling a bit down on myself at the time.) In the terms of “Geeks, MOPs, and sociopaths in subculture evolution,” what I wrote would make me a “MOP,” a passive cultural consumer. In many subcultures, though, I was a “geek.” In some, I was a “fanatic” more specifically. That means not that I was blinded by an ideology, but that I put a lot of energy into supporting a subculture. In others, I was a “creator”: devising and leading large public Pagan rituals, for example. Arguably I was also sometimes a “sociopath.” For example, it is technically true that I’m bi, but my leadership role in bisexual political activism was motivated more by hopes of romance and/or sex with the exciting, intense women I found there. That led to my writing Meaningness, as I explained in “Who was that friend, who inspired the book Meaningness?”

I don’t know whether this story is true. I think I remember hearing it from my mother. She was an anthropologist. That probably explains a lot about me.

What a fun date. Hopefully you don’t get too many neonazies with auto alerts for 14/88 stuff here.

This reads like an early diagnosis of what we now experience as ambient fragmentation. Where meaning still exists but no longer arrives bundled with a place to stand. The loss was the bounded contexts that could hold sensemaking capacity without demanding universality.