The common civilizational pattern of a separate priesthood and aristocracy casts light on current political dysfunction.

This video follows “Nobility and virtue are distinct sorts of goodness.” You might want to watch that one first, if you haven’t already.

These are the first two in a series on nobility. There will be several more. Subscribe, to watch them all!

Transcript

Many successful civilizations have two elite classes. They hold different, complementary, incommensurable forms of authority: religious authority and secular authority.

This usually works reasonably well! It’s a system of checks and balances. Competition and cooperation between the classes restrains attempts at self-serving overreach by either.

I think this dynamic casts light on current cultural and political dysfunction. At the end of this video, I’ll sketch how it has broken down in America over the past half century—perhaps not in the way you’d expect! In following videos, I’ll go into more detail, and suggest how we might respond.

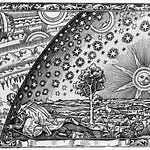

Archetypically, historically, and allegorically

First, though, I’ll describe the dynamic archetypically, historically, and allegorically.

Archetypically, the two elite classes are the priesthood and the aristocracy. They hold different types of authority (and therefore power).

Priests hold authority over questions of virtue. They claim both exceptional personal virtue and special knowledge of the topic in general. On that basis, they dictate to everyone else—both aristocrats and commoners—what counts as goodness in personal life, and in local communal life.

Kings, or more generally a secular ruling class, hold authority over the public sphere. They claim to exercise their power nobly. They may consider that’s due either to innate character, strenuous personal development, or both. That would justify a legitimate monopoly on the use of violence, and authority to dictate the forms of economic and public life.

This typically leads to an uneasy power balance. The two classes need each other, but also are perpetually in competition. Priests provide popular support to the aristocracy by declaring that they rule by divine right—or proclaim that the gods are angry with aristocratic actions, so virtue demands opposing them. Priests reassure aristocrats that they, personally, will have a good afterlife—or warn of a bad one when they don’t do what priests say they should. Priests depend on the aristocracy for most of their funding, for protection, and for favorable legislation. The aristocracy can increase or decrease that, or threaten to.

It’s extremely difficult for either class to displace the other entirely. Things generally seem to go better when they cooperate. Especially when priests are, in fact, reasonably virtuous, and the nobility are reasonably noble. Otherwise, they may collude with each other against everyone else.

Sometimes, though, one side or the other is dominant, and subordinates or even eliminates the other class.

Theocracy, in which priests usurp the role of secular rulers, does not go well. Priests try to increase their authority by inventing new demands of virtue. In the absence of secular restraining power, there is no limit to this. Most people do not want to be saints. When priests seize secular power, they unceasingly punish everyone for trivial or imaginary moral infractions. This is the current situation in Iran, for example. It’s bad for everyone except the priests. I expect it is unsustainable in the long run. Eventually there comes a coup, a revolt, a revolution, and the priests get defenestrated. (That’s a fancy word for “thrown out of a window.”)

Secular rulers taking full control of religion also does not go well. A classic example was Henry VIII. He rejected the Pope’s supreme religious authority and seized control of the Church. He confiscated its lands and wealth, dissolved its institutions, and summarily executed much of its leadership. He was able to do that through a combination of personal charisma; the power and wealth that came with kingship; and the flagrant corruption of the Church itself, which deprived it of broad popular support.

After clobbering the Church, Henry’s reign, unconstrained by virtue, was arbitrary, brutal, and extraordinarily self-interested. Economic disaster and political chaos followed.

Henry was succeeded by his daughter Mary, England’s first Queen Regnant. She used her father’s tactics to reverse his own actions. She restored the Church’s wealth and power through brutal and arbitrary executions. For this, she was known as “Bloody Mary.”

She was succeeded by her younger sister Elizabeth I. Elizabeth re-reversed Mary’s actions. She established the new Church of England, designed as a series of pragmatic compromises between Catholic and Protestant extremists.

Elizabeth was, on the whole, a wise, just, prudent, and noble ruler—which demonstrates that the archetype of a Good King has no great respect for sex or gender. Likewise, the reign of “Bloody Mary” demonstrates that women are not necessarily kinder, gentler rulers than men.

How modernity ended, and took nobility down with it

Allegorically, archetypically, such colorful history can inform our understanding of current conundrums. You might review what I’ve just said, and consider what it might say about American public life in 2025.

Now I will sketch some more recent, perhaps more obviously relevant history.

On the meaningness.com site, I have explained how modernity ended, with two counter-cultural movements in the 1960s-80s. Those were the leftish hippie/anti-war movement and the rightish Evangelical “Moral Majority” movement. Both opposed the modernist secular political establishment, on primarily religious grounds. Both movements more-or-less succeeded in displacing the establishment.

Revolutions can be noble. I think the 1776 American Revolution was noble. It was noble in part because the revolutionaries respected the wise and just use of legitimate authority. They accepted power, and ruled nobly after winning.

The American counter-cultural revolution two hundred years later refused to admit the legitimacy of secular authority. Its leaders instituted a rhetorical regime of permanent revolution. For the past several decades, successful American politicians have claimed to oppose the government, and say they will overthrow it when elected; and, once elected, they say they are overthrowing it, throughout their tenure.

This oppositional attitude makes it rhetorically impossible to state an aspiration to nobility. You can’t uphold the wise and just use of power if you refuse to admit that any government can be legitimate. Nobility, then, was cast as the false, illusory, and discarded ideology of the illegitimate establishment. In the mythic mode, we could say that everyone became a regicide: a king-killer. After a couple of decades of denigration, nearly everyone forgot what nobility even meant, or why it mattered, or that it had ever existed outside of fantasy fiction.

Secular authority in the absence of nobility

Secular authority persisted, nonetheless. What alternative claim could one make for taking it? There are two.

First, there is administrative competence. This was an aspect of nobility during the modern era, which ended in the 1970s. “Modernity,” in this sense, means shaping society according to systematic, rational norms. Developed nations in the twentieth century depended on enormously intricate economic and bureaucratic systems that require rational administration. One responsibility of secular authority is keeping those system running smoothly.

Both counter-cultures rejected systematic rationality, as a key ideological commitment. However, it was obvious to elites, inside and outside government, that airplanes need safety standards, taxes must be collected, someone has to keep the electric power on. A promise of adequate management was key to institutional support from outside elites during the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. That kept a new establishment in power.

However, it lacked popular appeal. Managerialism is not leadership, which is another aspect of nobility—one that more people more readily recognize. And, as modernity faded into the distant past, beyond living memory, later generations failed to notice that technocratic competence matters: because we will freeze or starve without electricity.

Accordingly, virtue has displaced competence in claims to legitimate authority. Initially, this came more from the right than from the left. The 1980s Moral Majority movement aimed for secular power, justified by supposedly superior virtue. Some American Christians explicitly aimed for theocratic rule.

However, for whatever reasons, the left came to dominate virtue claims instead. They gradually established a de facto priesthood: a class of experts who could tell everyone else what is or isn’t virtuous. Initially it claimed authority only over private and communal virtue; but increasingly it extended that to regulate public affairs as well. In some eyes, it began to resemble a theocracy. It did increasingly display the theocratic characteristics that I described earlier. And, in punishing too many people for too many, increasingly dubious moral infractions, it overreached; and seems now to have been overthrown.

Regicide and defenestration, OK; but then what?

This religious analogy was pointed out by some on the right, fifteen years ago. I think there is substantial truth in it. However, I think they are terribly wrong about the implications for action. I’ll discuss that in my next post.

If the ruling class is neither noble nor even competent, but can claim only private virtue, then metaphorical regicide (or defenestration for the priesthood) is indeed called for. That’s justified whether their claims to virtue are accurate or not. Whichever opinion about trans pronouns you consider obviously correct, holding that opinion does not justify a broad claim for secular authority.

But… now what? Perhaps there is some noble prince in waiting, biding his time, cloaked in obscurity, like Aragorn, rightful King of Gondor?

More likely, some commoners will need to reclaim, re-learn, and rework nobility. As did Frodo, son of Drogo, “a decent, respectable hobbit who was partial to his vittles.”

Maybe… that should be you! As I’ve pointed out before, you should be a God-Emperor. Maybe now is a good time to get started on that?

Share this post