Four kinds of philosophy I don’t do

If my work resembles philosophy, specifically which? It’s not any of those.

“Undoing philosophy” has two motivations. Most of it intends to help you free yourself, as much as possible, from the harmful effects of philosophy.

Chapter 4, begun here, has the second motivation: to help you get the best use from my work, by pointing out how it isn’t philosophy.

A common mistake is to read it as philosophy. If you do that, you risk systematically misunderstanding it, resulting in missing most of its possible benefit.

Alternatively, if have no interest in philosophy, or scorn it as all nonsense, you might pass over what I have written, believing it is that. Then you’d miss discovering practical pointers which might improve your life.

When I insult philosophy on social media, the response is often incredulous:

But you do philosophy yourself! That’s your whole thing! The Meaningness book and the meta-rationality one are philosophy! What else could they be?"

I mostly don’t use philosophical methods or concepts. The motivations for my work, and its value, are quite different from philosophy’s. There’s some overlap in topics, but psychology and religion also cover those, so philosophy has no unique claim on them.

There’s no official definition of philosophy against which to compare my writing, but these factors seem sufficient to make it clear that they are dissimilar.

This chapter has three parts:

“Four kinds of philosophy I don’t do.” Philosophy is diverse, with many traditions, positions, and subfields. I compare my stuff with the four that may seem most similar: antiphilosophy, phenomenology, scientism, and empiricism.

“What isn’t philosophy: a meta-rational explanation.” Philosophy has no coherent definition of itself. That makes it difficult to say what isn’t philosophy using philosophical methods. I apply meta-rational methods instead, which work better for understanding marginal cases. I discuss several criteria by which something might be categorized as philosophy or not: institutional position, institutional opinion, social and historical linkages, author’s intention, topics discussed, motivations, and methods. I conclude that, considered in the light of each of these, my work is not philosophy. (But what is it, then?)

“Does this chapter explain even itself?“ More than most of my writing, this chapter itself may seem philosophical. So, is it? If so, it is a self-defeating performative contradiction! I evaluate the chapter’s philosophy-ness in the light of the discussion in the two previous sections.

THE OVERALL TITLE of this chapter is “I don’t do philosophy.” For this Substack version, I’ve split it into three posts. This one includes the introduction, which you’ve just read, and the first part. That’s the one about types of philosophy I don’t do, and how and why I don’t do them.

If you have landed on this post without context, you might want to read chapters 0, 1, and 2 of “Undoing Philosophy” first. Chapter 3 will explain how philosophy causes great harm to our everyday way of being, but I haven’t finished writing it yet. The harms are pervasive (so where to even start?) and dire (so how to convey how damaging they are?) but insidious and reflexively overlooked (so how to draw attention to them specifically?).

Antiphilosophy: a near miss

Nothing I’ve said in the previous chapters is in any way new. If you read more than a little philosophy, you could not miss noticing that it’s mostly blatantly wrong, absurd nonsense, or technical nit-picking about dubious abstractions no one outside some philosophical subsubsubfield knows or cares about.

You say “all philosophy is bad,” but you say like some philosophy, like Heidegger and Wittgenstein. You are just using “philosophy” to mean “stuff I don’t like!”

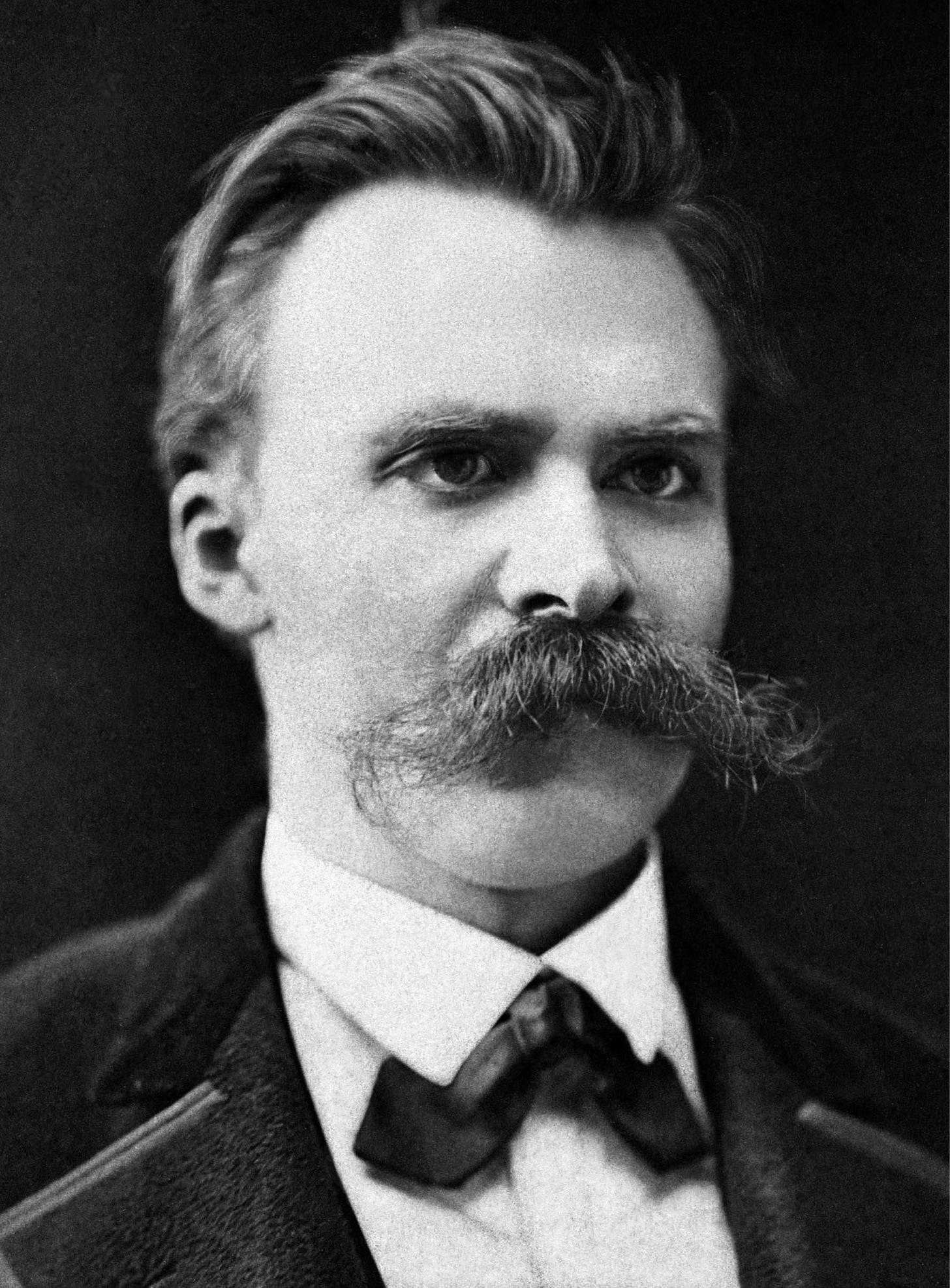

The philosophers I respect and am influenced by were sharp critics of philosophy overall, and wanted to radically reform or replace it. They are sometimes called “antiphilosophers.” Prominent examples include Nietzsche, the American Pragmatists, Heidegger, Wittgenstein, and Foucault.

These were perceptive guys, and they had extensive backgrounds in relevant non-philosophical fields. They noticed that the ways non-philosophers relate to meaningness aren’t explained by philosophy. Also, that those ways were changing, as both Christianity and rationalism had begun to discredit themselves. The antiphilosophers investigated examples of these phenomena and came to useful understandings.

The problem, however, is that they were still doing philosophy. They mainly discussed large, vague abstractions, whose connection (if any) with reality is unclear, and about which anyone can argue anything. Their main method was arguing about philosophy, which is what philosophy mainly is, and so creates more philosophy. They were unwilling to desacralize philosophy; to outright reject it as harmful and stupid.

The main value I find in antiphilosophers’ work is negative. The reasons they give for rejecting major chunks of earlier philosophy seem right. Their positive proposals, about how things are and how to proceed, mostly seem too abstract to be useful. They also mostly seem wrong, when clear enough to evaluate.

The antiphilosophers would have done more and better work if they had not been doing philosophy. The antidote to philosophy is not more or better philosophy. The main antidote is to not do it when you are tempted to. Just walk away from the tabletop piles of intellectual fentanyl. Forget about it. There’s nothing good there.

If you are addicted—as we all are, due to philosophy contaminating our ordinary everyday thinking—this may be difficult. Antiphilosophy does put a fence around the table and sets some of the fentanyl on fire. (Leave the premises immediately! Don’t inhale the fumes.)

The secondary antidote is to uncover and undo the wrong philosophical assumptions and patterns of reasoning that pollute our cultural background understandings. This requires reading and understanding philosophy—taking care not to do any. It risks inhaling some accidentally.

It’s a dirty, dangerous job, and I don’t see why I have to do it. But someone has to, and I took a vow to save all sentient beings, so here we are.

(The final chapter of “Undoing Philosophy” has more about that second antidote, and how we can free ourselves from the stuff.)

This twitter thread explains how and why Heidegger’s attempt to reform philosophy failed. He tried to get back behind a key error, the invention of metaphysics at the dawn of Greek history. Then he hoped to reclaim thinking in its pristine state, as it was before that. That recapitulated an even earlier error: the wistful certainty that identifying an original cause would give us understanding and therefore control.

Tentatively I’m planning an entire post about this: how philosophy went wrong at the very beginning, and why. (Snake goddesses are implicated.) This may help understand how it continues to damage our everyday thinking, feelings, and interactions. Or, it may just recapitulate Heidegger’s mistake…

Phenomenology: another near miss

As philosophy goes, the stuff I do might most accurately be mistaken for phenomenology. My main method is to observe details of something in the actual, everyday world and explain what I find. Phenomenology is something like that, but puts much less weight on concrete specifics, and employs far more concepts, abstractions, metaphysics, and reference to previous philosophy.

“Phenomenology, minus metaphysics, and from a non-subjective point of view, plus a practical orientation to concrete details of the ordinary world, and with a restoration of myth relativized by meta-rationality” would not be a completely inaccurate description of my work. With all those alterations, I don’t think it continues to counts as philosophy, but this may not be a point worth arguing.

“Phenomenology” names a topic, a method, and a historical movement.

The topic, as originally stated at least, was “the structures of consciousness as experienced from the first-person point of view.” That assumes a wrong metaphysics: a hard separation between subject and object, appearances and reality, or phenomenon and noumenon.

Phenomenology’s original method was introspecting about consciousness. That is notoriously unreliable. It’s prone to elaborating metaphysical fantasies, and doesn’t converge toward interpersonal agreement.

Phenomenology as a movement was valuable, in gradually and partially redirecting philosophers’ attention away from hypothetical metaphysical fantasies, toward indisputable concrete phenomena. It made significant progress: from phenomenology’s founder, Husserl, through his student Heidegger, to Merleau-Ponty. These are considered the three main figures in the field—along with Sartre, about whom the less said the better.

The beginning was not promising. Husserl was mostly lost in metaphysical speculation (essences, Brentano’s intentionality, transcendental idealism). To discover the structures of consciousness, he claimed to use special forms of cognition: “epoché,” “eidetic reduction,” and “transcendental reduction.” These would be misleading if they were even possible, which they probably aren’t.

Heidegger, in his main work Being and Time, wrestled with the supposed question of “the meaning of Being.” That’s the most abstract and metaphysical problem there is (which is why Heidegger tackled it). Inasmuch as it’s a meaningful question at all, his answer (authentic resoluteness in being-toward-death) was wrong—as he acknowledged in his later work.

However, he made dramatic sideways progress, along his way to the wrong endpoint. As an antiphilosopher, he explicitly rejected metaphysics in its entirety, and denied major metaphysical assumptions that had gone largely unthought and unchallenged since Plato. In this, he was significantly influenced by Zen and Taoism. As in those, he rejected the separation of subject and object, and the assumption that consciousness is the essence of human being. As in Zen and Taoism, he considered mundane objects and activity—hammers and hammering were his main example—primary. Concepts, rationality, and contemplation are secondary, derivative modes of being.

This inversion redirects our attention: away from pointless philosophical pseudo-problems in imaginary Ideal worlds, toward the actual world. Attention to the actual world may yield insights that we can use in our actual lives and projects.

Being and Time was still so abstract that it didn’t do that. However, most subsequent work in Continental philosophy might count as “footnotes to Heidegger,” and some of it got much more concrete.

Merleau-Ponty’s main work, Phenomenology of Perception, founded the field of “4E psychology”: embodied, embedded, enacted, and extended. (That name came much later, but he was there first.) He further broke down the traditional metaphysical dualisms such as thought and action, sensation and perception, mind and body, in favor of an interactionist view—neither subjective nor objective.

“The mind/body problem” usually considers two vague metaphysical entities. “The mind” is mostly made of propositions, and “body” just means “matter, insofar as it somehow, mysteriously, relates to propositions.” Merleau-Ponty took “body” seriously and specifically, as including gloppy tubes and squishy blobs. Philosophy turns away in revulsion from such details, because they are grossly physical, blatantly non-metaphysical, and therefore ugly, trivial, and beneath consideration. Merleau-Ponty explored specific “mental” phenomena, such as sexual desire. He found it significant–as I do—that lust and sexual pleasure can’t be separated from sexual anatomy and physiology. “The flesh is at the heart of the world.”1

Phenomenology of Perception drew extensively from Merleau-Ponty’s knowledge and practice of non-philosophical fields, including neurophysiology; psychology empirical and clinical, cognitive and developmental; anthropology; and linguistics. Merleau-Ponty is officially counted as a philosopher, and the book as a work of philosophy; but he was employed as a professor of child psychology.

This is a pattern I will return to: philosophers can do good work when it’s not philosophy, because they are attending to nitty-gritty specifics of the actual world.

Not scientism, that’s an undead philosophical eternalism

When I say “philosophy is bad,” aggrieved amateur philosophy enthusiasts often mistakenly dismiss that as scientism. To be fair, many dismissals of philosophy are motivated by scientism, although mine is not.

Scientism is the philosophical position that Science! is the only valid source of knowledge. By “Science!” I mean a simplistic, metaphysical belief that The Scientific Method is universally applicable and Correct. (There is no such method.)

“Any claim not backed by Science! is either false, or meaningless verbiage, so philosophy is bad” is the standard claim. (Usually there’s some half-baked invocation of “falsifiability” in there.) This was a mainstream view a hundred years ago. It is silly, and no longer held by anyone serious.

You don’t need science to see that your socks are blue. Everyone has lots of reliable knowledge that has nothing to do with either science or philosophy. You may know a lot about bicycle repair, Chinese food, office politics, the Meiji Restoration, or Proto-Indo-European verb inflection, for example.

At a slightly deeper level, scientism is silly because science is inherently inadequate to address most matters of meaningness, such as ethics, purpose, and value.2 Empirical facts about how people do those things can inform our understanding, but not determine it.

Scientism-ists and philosophy enthusiasts both seem to believe there are fundamentally three Theories Of Everything, namely religion, Philosophy!, and Science!. If you reject religion, you have to pick one of the other two brands. (This three-way opposition originated with Auguste Comte, a hugely influential philosopher of the mid-19th century. He’s mostly forgotten now, but his wrong ideas entered our cultural background assumptions as toxic philosophical effluents. They are still influential in popular misunderstandings.)

Online Scientism-ists and Philosophism-ists enjoy endlessly insulting Religion-ists, and each other, for making the wrong choice. Science! and Philosophy! proponents are both typically young men. Maybe this explains the imaginary forced choice? They are cheering for rival football teams, not coherent intellectual systems.

Science! and Philosophy!, similarly to most religions, are eternalisms: belief systems that promise certainty, understanding, and control. Eternalisms are attractive as defenses against the emotionally unacceptable nebulosity of meaningness, but they can’t deliver on their promises.

Not empiricism, that’s not even a thing

“Rationalism,” in ordinary current non-technical usage, is the overestimation of the power, reliability, and value of rationality. That’s what I mean by it too. There are also various specialized uses of the word.

An extreme version is the philosophical doctrine that reasoning is the only source of knowledge. In this case, the explicit claim is that perception is not a source of knowledge. This is obviously fantastically false. However, some philosophers of past centuries claimed to believe it, although it seems extremely improbable that any of them actually did. This was paranoia, motivated on noticing that perception is not entirely reliable.

Some other philosophers, who noticed that you know that your socks are blue because you can see they are, went to the opposite extreme. They claimed that perception was the only source of knowledge. In this case, the explicit claim is that reasoning is not a source of knowledge. This was called “empiricism.” It is obviously fantastically false. However, some philosophers of past centuries claimed to believe it, although it seems extremely improbable that any of them actually did. This was paranoia, motivated on noticing that reasoning is not entirely reliable.

Then for a couple of hundred years rationalists and empiricists argued with each other, because that is what philosophers do.3

The dispute didn’t get settled until the early twentieth century, when most philosophers reluctantly admitted that perception and reasoning are both sources of knowledge, and—astonishingly!—you can even use both at the same time. Essentially no one has held either of the extreme positions for a century. Nowadays, “rationalism” and “empiricism” are often used to mean the same thing: “it’s good to use both perception and reasoning.” In some contexts, the two terms may suggest an enthusiasm for one over the other.

The extreme versions are often given as definitions of “rationalism” and “empiricism” in current pseudo-authoritative online sources and introductory texts, although these uses are totally obsolete.

Anyway, sometimes when I publicly reject “rationalism,” by which I mean “overvaluation of rationality,” someone insists that this means I must advocate “empiricism,” because they have read that it’s the alternative. If “empiricism” means “taking visible facts into account,” then I am an empiricist; and so is everyone else.

But “empiricism” is not meaningfully an alternative to rationalism, and there is no such philosophical position any longer.

The second section of “I don’t do philosophy” is “What isn’t philosophy: a meta-rational explanation.” Read it next!

Quoted from his The Visible and the Invisible. Phenomenology of Perception has more on sexual desire, though.

More philosophically sophisticated and academic readers will recognize here that I am also denying that my stuff comes under the similar, but more sophisticated and academic, category “positivism.” So far, no one has accused me of positivism, unlike accusations of scientism, so I won’t go into that further.

Or, this is what historians of philosophy now describe as “the standard narrative.” It’s common in histories of philosophy to present rationalism and empiricism as clearly opposed, to categorize Enlightenment-era philosophers into these two camps, and to attribute extreme positions to them. This was taken for granted during the twentieth century, but more recent historical research suggests that it is false, or at minimum a gross oversimplification. The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy’s “Rationalism vs. Empiricism” article acknowledges that “almost no author falls neatly into one camp or another,” and attempts to clarify. The binary classification was a motivated invention, for propaganda purposes, in the nineteenth century. It persisted through the twentieth because it was a convenient simplification of a lot of confusing nonsense. That had become obsolete and irrelevant, but you still had to summarize it in university courses because Great Philosophers are holy. Geeks who enjoy this sort of thing will enjoy Alberto Vanzo’s “Empiricism and Rationalism in Nineteenth-Century Histories of Philosophy,” Journal of the History of Ideas, Volume 77, Number 2, April 2016, pp. 253-282.

I love how commenters are warning you to stay away from the tar baby of philosophy. The more you strike it, the more it sticks to you!

But I am amazed how the progression of your studies mirrors my own. I spent my twenties obsessively reading Kaufmann’s Nietzsche translations, to the point where I could not only tell you from which books his more famous quotes came, but in some cases, even the numbered section it was in.

Then I tried reading Hegel, Husserl, Merleau-Ponty, etc. I read a book explicating Hegel’s extremely long and verbose Phenomenology of the Spirit, that was longer than the Phenomenology itself. Husserl was as opaque as a brick wall, but I found some of Merleau-Ponty’s less philosophical musings about the world very interesting and worth reading.

Same reaction to A.N. Whitehead. Whitehead had a very interesting and intellectually wide-ranging career, and his popular books like Science in the Modern World were a very fruitful read, but his magnum opus, Process and Reality, was a huge head-scratcher. I read it twice, no comprehension either time.

Later I felt justified in my confusion when I read a comical anecdote in one of Richard Feynman’s books. During a scientific dry spell, Feynman attended a philosophy course where they were studying Whitehead. He asked question after question, but could never get the teacher to pin down exactly what Whitehead was trying to say. It was just confusion after confusion.

contra the critics who have also posted comments, I support your effort to undo philosophy, for the reasons you state, and for some of my own which you haven't stated. at minimum it's a useful reflection for people like you and I who have had the experience you describe of reading something claimed to be profound and finding it to be delusive nonsense. grappling with the dissonance of that experience seems fruitful to me, whatever the outcome.

I think I've recommended this before, but once again I feel called to recommend History as a System by José Ortega y Gasset (https://www.goodreads.com/en/book/show/778458.History_as_a_System_and_other_Essays_Toward_a_Philosophy_of_History)

Ortega was a contemporary of Heidegger, a Spanish Republican (contrasted with Heidegger's Nazism), and a critic of Heidegger. He was a "public intellectual" and had all the baggage that goes along with that, especially the common interpretation of his most famous work - Revolt of the Masses - being framed as an anti-populist polemic, which it kinda is, but that's missing the real context and purpose of the essay. That's besides the point.

I want to point at History as a System because I think of it as Ortega's most central/foundational essay in his entire way of thinking and is the most explicit statement of his meaning-making framework out of all of his writing. It could broadly be counted as an entry in the "anti-philosophy" movement, but it has a different orientation entirely. Rather than trying to point out fatal flaws in formal systems (as Wittgenstein did), or trying to point out problematic metaphysical assumptions (as Heidegger did), Ortega is trying to bushwhack his way into a completely new (to Modernity, anyway) way of being and it's associated metarational framework.

A good one line summary of the work is "Yo soy yo y mi circunstancia" (I am myself and my circumstances). His view of self is that it's a co-creation with circumstances, which are inherently and necessarily historical. He positions the storytelling part of history as the underlying driver of meaning-making and examines the idea of a historical "project" as the vessel for the meaning-making efforts of humanity. Ortega wasn't any kind of Buddhist nor did he directly engage with it in the same way that Heidegger did. He seems to have independently converged on a view that is resonant with the view from Buddhism that emphasizes mutual interdependence and relationality (i.e. non-dualism).

He focuses in particular on two ideas, one that he labels "Vital Reason", that I would summarize as an early 20th century version of what we now know as Meta-Modernism or Post-Rationalism. The other important idea is a view of history as being driven by cycles of crisis and renewal, a macrocosm at the societal level of what individuals experience in their own lives and psyches.

I think you would enjoy his work quite a lot. It's far more accessible than Heidegger (that's a low bar to clear though) and to me feels much more humane and much more, well, prophetic. He was also attempting to undo philosophy, in his own way, without explicitly naming it such. I think his heartfelt desire was for people to be able to make sense of their own lives, and the world they're living in, such that they can determine for themselves what things are supposed to mean, liberating themselves from the oppression of the broken meaning-making of the old frameworks (Church and State) so that they might pursue the new historical project of building a humane society.