Vajrayana resolves confusions about Nietzsche’s master vs. slave morality distinction. Those rest on wrong metaphysical assumptions at the root of Western thought. Dropping these unthought axioms reveals glorious possibilities they have obscured.

My nobility arc includes this post, and several related ones. You might want to read those too!

A recent post by Scott Alexander, “Matt Yglesias Considered As The Nietzschean Superman,” has prompted much discussion. It is about Nietzsche’s master morality vs. slave morality distinction.

Or, at least, it’s about popular misunderstandings of the distinction. However, it doesn’t matter what Nietzsche actually said. He’s dead, so he can’t act on whatever he thought.

What does matter is people trying to justify their actions based on their ideas about master and slave morality. Those ideas are bad, and have led to wrong-doing up to and including genocide.

How such ideas relate to Nietzsche’s writing is irrelevant to their badness. And, in any case, it’s hard to say, because he was confused and going insane while trying to work it out, and had a permanent mental breakdown before finishing, so what he wrote is incomplete and a muddle.

My post offers a better way to understand the issues Nietzsche grappled with, and better ways of acting from that understanding.

What seems to be the problem here?

The two foundations of the Western tradition are Ancient Greek philosophy and Christianity. Nietzsche observed that they have different conceptions of goodness, which he called “master morality” and “slave morality.” That was unfortunate, because the words “master” and “slave” are inaccurate as descriptions. They’re also triggering, which makes it harder to think clearly about the distinction.

Less obviously, and more seriously, it was unfortunate because the distinction isn’t about morality at all—as I’ll explain later in this post.

Nietzsche considered that slave morality had come to dominate in modernity, which was a problem because the Greek and Roman “master” understanding seems right in some ways, and the Christian “slave” one seems limited or wrong in some ways. However, the master morality is also obviously wrong in some ways, and Christian morality has much to recommend it. So he wanted to take what was correct in both and combine them somehow, but couldn’t figure out how to make that work.

If you are unfamiliar with this, the Wikipedia article gives an easy, short explanation.

Alternatively, here’s Scott’s summary:1

The excellent noble exhibits master morality by delighting in being strong, healthy, and virile. He lives in a beautiful palace and wears shining golden armor. He may be cultured, sophisticated, or even brilliant. He’s great at everything he does, and harbors ambitions to become even greater, maybe conquer a kingdom or two. He’s powerful, skillful, and awe-inspiring.

Slave morality says that the strong are tyrants, the rich are greedy, and the ambitious are puffed-up braggarts. God loves the humble. The worst thing you can do is try to pridefully rise above your fellows; the best thing you can do is to lessen yourself, through methods sacred (fasting, celibacy, self-flagellation) or mundane (giving to charity, serving your fellow man). It doesn’t openly challenge the individual to ensmallen herself. It just arranges the incentives so that they have to.

The essence of slave morality is the herd instinct—a distributed mob of people saying “you had better ensmallen yourself if you know what’s good for you.” An individual might ensmallen themselves because of personal fealty to slave morality. But more often they’re doing it lest they look like Tall Poppies—people who defect from an unspoken social consensus that everyone ensmallen themselves, and so earn the envy and hatred of their peers.

Slave moralists interpret any attempt to talk about good things, pursue good things, or achieve good things as a bid for status, and pre-emptively try to cut it down. If someone makes too much money, they’re a shady profiteer; if they’re too smart, they’re an IQ-obsessed techbro; if they’re too pretty, they’re a slut. The goal is to unite all the envious people into a Tall Poppy Police who agree that successful people suck, to prevent anyone from potentially judging the slave moralist as worse.

Even if you find it easy to avoid taking on slave morality yourself, you need to be prepared to live in a slave morality world.

The master-vs.-slave morality story comprises a mass of confusions. For one, there’s an assumption that these two possibilities are somehow exhaustive, so we have to either pick one or else find some middle position or compromise. Even within the Western tradition, there are many recommended ways of being that don’t fit either “morality.”

At a deeper level, Christianity and the Greeks share many metaphysical axioms that are wrong, and which are foundational for the Western tradition, which is therefore pervasively broken (despite all its considerable virtues).

Fully sorting out “master vs. slave morality” would, therefore, require a radical reanalysis of the entire Western tradition, and then reassembly without its wrong metaphysics. That is what Nietzsche set out to do, but unfortunately could not finish, due to his mental breakdown. I’m not going to finish it either, because a complete replacement for Western thought won’t quite fit in a Substack post. Instead, I’ll sketch an approach in a somewhat unsystematic and informal way, rather than laying out a clear, detailed logical argument.

Better is better

Scott attributes to

the insight that good things are good. I would put this in a more confronting way: better things are better.According to Scott, the motivation for one sort of contemporary slave morality is to never have to feel inferior to anyone in any way. You can attempt to accomplish that by denying that anyone is better than anyone else in any way. Specifically, anyone who might appear to be superior in some way is actually extremely bad because they are oppressors or some such species of villain. This entails the stance that better is worse. That is—obviously—false and harmful.

It also doesn’t fool anyone, including you. It just convinces your self that you are inferior, and are lying to cover it up. For that, you rightly feel secret shame.

Since so many people now adopt the better-is-worse stance, Yglesias suggests that, as a pragmatic compromise between master and slave morality, we have to humor slave moralists by publicly pretending they are right, while privately celebrating and working toward excellence. Scott’s summary:

A final secret of this compromise is that master morality and slave morality aren’t perfect opposites. Master morality wants to embiggen itself. Slave morality wants to feel secure that everyone agrees embiggening is bad. The compromise is that we all agree embiggening is bad, but leave people free to do it anyway.

Yglesias asserts that this doubletalk is the essence of liberalism, democracy, and all good things.2

I think it is neither morally correct nor pragmatically necessary. Even at some personal cost, we should assert the obvious: that better is better.

Our deepest fear is not that we are inadequate. Our deepest fear is that we are powerful beyond measure. It is our light, not our darkness, that most frightens us. We ask ourselves, who am I to be brilliant, gorgeous, talented, fabulous? Actually, who are you not to be? You are a child of God. Your playing small doesn't serve the world. There's nothing enlightened about shrinking so that other people won't feel insecure around you. We are all meant to shine, as children do. We were born to make manifest the glory of God that is within us. It's not just in some of us; it's in everyone. And as we let our own light shine, we unconsciously give other people permission to do the same. As we're liberated from our own fear, our presence automatically liberates others.3

Vajrayana is to Buddhism as Nietzsche to the Western tradition

Vajrayana is the unusual branch of Buddhism I write about on Vividness and Buddhism for Vampires. It includes Buddhist Tantra (the path of the transformation of energy) and Dzogchen (the way of instantaneous self-liberation).

Vajrayana includes a comprehensive critique of mainstream (“Sutric”) Buddhism. This critique is strikingly parallel to Nietzsche’s critiques of rationalism and Christianity, the two Western foundational ideologies.

The fundamental principle of Sutric Buddhism is renunciation, based on revulsion for the world. Nietzsche used Sutric Buddhism—the only type he knew—as an example of “slave morality.” Revulsion and renunciation are also major themes in Christianity, and expressions of what he considered Christian slave morality.

Vajrayana rejects and inverts renunciation. It celebrates beauty, pleasure, involvement, freedom, power, mastery, and—explicitly—the aristocratic ideal of nobility.

Vajrayana also rejects many of the fundamental metaphysical axioms of Sutrayana. Many of those are found also in the Western tradition. Vajrayana is, therefore, valuable as a broad challenge to our fundamental, unthought assumptions. I’ll discuss only a few; ones relevant to master vs. slave morality discussion.

Enlightened hero

Vajrayana also retains many aspects of mainstream Buddhism. Particularly relevant to this discussion: Vajrayana affirms the mainstream bodhisattva ideal, and incorporates and strengthens it.

A bodhisattva is someone who dedicates their entire life to the benefit of others. The word is often (mis)translated as “saint.” The difference is that a bodhisattva is meant to do good, not merely to be good. Holiness is insufficient. Effective heroism is required.

Vowing to act as a bodhisattva is foundational for Vajrayana. This already suggests it may hold a resolution to the supposed problem of reconciling master and slave moralities.

The term “bodhisattva” can be a pun. In the scriptures, it’s also often spelled “bodhisatva,” pronounced the same way. “Bodhi” means “wakefulness” literally; in Buddhism, it means “enlightenment.” “Sattva” with two ts is “being,” but “satva” means “warrior” or “hero.”

So a bodhisatva is a heroic, enlightened warrior: someone who is willing even to kill or die for the benefit of others.

In Ancient Greece, and in Medieval India, and in modern Europe up through the First World War, the aristocracy were the military caste. The Vajrayana ideal fuses Buddhist values with those of the Kshatria, India’s aristocratic-warrior caste. Maybe then it can provide a resolution to Nietzsche’s problem?

You can be noble—and often you are

In contemporary English, “noble” refers both to the hereditary aristocracy and to excellence in beneficence. It is noble to dedicate one’s life to healing the sick, empowering the poor, making great art, or clearing needless regulatory obstacles to carbon-free power.

But nothing so elevated is required. Quoting myself elsewhere:

Nobility is the aspiration to manifest glory for the benefit of others. Nobility is using whatever abilities we have in service of others. Nobility is seeking to fulfill our in-born human potential, and to develop all our in-born human qualities.

Everyone could be noble—and at times all of us are noble. It is not an accomplishment; it is a stance. But nobility is not easy. It is not easy to hold the intention continuously. It is not easy to abandon our laziness. To be noble is not special—but it is extraordinary.

Nobility takes itself for granted, and needs no confirmation. When we have that intention, we have no doubt of it.

Mere goodness is not nobility. Being “morally correct” in an ordinary, unimaginative, conformist way may be an excuse for avoiding the scary possibility of extraordinary goodness, or greatness. Doing good in a showy way can be a strategy for convincing ourselves, or others, that we are special. Celebrity charity work often seems to be that. Of course this is better than many other ways of trying to be special, but it somewhat misses the point. Specialness serves in order to rise, whereas nobility rises in order to serve.

The idea of being “noble” may sound remote or ridiculous. However, it is actually available to all of us in every moment, simply by choosing it. It is frightening; but to me it seems infinitely worthwhile.

Like most of my posts, this one is free. A few I paywall: as a reminder that I deeply appreciate paying subscribers—some new each week—for encouragement and support. It’s changed my writing from a surprisingly expensive hobby into a surprisingly remunerative hobby (although not yet a real income).

You are a leaf devil, not a concrete planter

A fundamental metaphysical axiom of the Western tradition is that we have, or are, “selves,” which are our permanent essences. “Selves” (or “souls”) choose what we do, and their qualities determine personal value, so we can be judged as good or bad.

Buddhism rejects that. Mainstream Buddhism, in different versions, says that your self does not exist, or it is “empty” (whatever that means—no one can explain clearly), or that it should not exist and you need to get rid of it, or analyze and transcend it, or unify it with Cosmic Oneness, or something.

Vajrayana inherits this “non-self” (anatman) doctrine, but transforms it. There is nothing fundamentally wrong with your self. “Ego” is not evil. Your self is not a spiritual obstacle.

Vajrayana retains what is right in the mainstream Buddhist metaphysics, that selves are not solid, permanent, separate, continuous, or defined. For Vajrayana, selfing is something we do, and lasts only as long as we’re doing whatever it is. We do different things, frequently, on a moment-by-moment basis even, depending on what’s happening around us and and our current purposes. One implication of this is that there are no good or bad people, only good and bad activities.

“Self” is always flickering in and out, fluidly reforming in our interactions. Recently, I described this with a vivid analogy. On the MIT campus, there is a large concrete planter in the middle of an outdoor walkway. When the wind rises, a vortex forms in the wake of the planter, and if it’s blowing hard enough in autumn, it becomes a leaf devil:

It picks up fallen leaves in a mini tornado, sucking them way up in the air. At the height of the season, maple leaves, brilliant red and gold, swirl up in a tight column, a dozen feet into the air, four feet across. It's magical! Memorable! Mesmerizing! It's glorious like nothing you have ever seen!

A self is not a solid fixed object like a concrete planter, but intermittent like a leaf devil: an interaction of matter and wind-energy, dissolving and reappearing depending on conditions.

It's not a thing; it's a dynamic pattern of activity. But unlike the leaf devil, I have many different patterns I self with. Different circumstances call forth different patterns, different "selves," different ways of being. How I am on a zoom call with a mentee, how I self, is different from how I self when talking with my spouse over dinner.

I have a different self in every moment. There's a Dzogchen practice of taking literally Heraclitus' maxim: "No man ever steps in the same river twice, for it's not the same river and he's not the same man." Dzogchen frames this in terms of the Buddhist doctrine of rebirth. "I," my "self," die and am reborn in every second, into a different world. This is astonishing! I am a new person, opening my eyes and beholding a fork for the first time in my life!

Since we have no fixed selves, since our selves re-form constantly, we can change dramatically, in an instant even: partly by choice, and partly in response to unusual circumstances.

Abhisheka: discovering you are an Enlightened God-Emperor

Vajrayana is a system of practical methods, not philosophy.

One of the most important methods is self-arising yidam: you experience yourself as a different person, a different self, who is enlightened. That person is a “yidam,” often explained as “a god,” which is not exactly accurate, but close enough for now.

OK, how? The first step is undergoing a ritual, called abhisheka in Sanskrit. In scriptural theory, abhisheka forcibly transforms your self into a yidam by putting you in extremely unusual circumstances. As originally performed, the ritual combined the imperial coronation ceremony of the Pala Empire—you are crowned as a god—with the transgressive sex and death magic of outcaste witches. It was utterly over the top, shredded any sense of ordinary self, and replaced that with the enlightened self of the yidam. Having been the yidam once, you retain the possibility, and there are methods to return later.

“Abhisheka” literally means “annointing,” which was the key moment in the ritual transformation of the heir to the imperial throne into the emperor. (Annointing is still the key moment in the ritual transformation of the Prince of Wales into King of England.) The Tibetan term is wang, “empowerment”: you gain the powers of the yidam.

So the theory is, or was, that abhisheka turns you into an enlightened god-emperor. If, as a bodhisatva, you intend to do good, becoming an enlightened god-emperor is a useful starting point.

(I told you you should be a God-Emperor. I meant it.)

Subsequently, under the Iron Law of Bureaucracy, the ritual was nerfed by administrators of monastic Buddhism, who found god-emperors inconvenient and disruptive for smooth institutional functioning. So you are not going to get the real thing. However, if you know what it was meant to be originally, you can try to experience the cheap plastic imitation as that, which may be quite effective.

Being an enlightened god-emperor is a good start, but if you fixed your identity on that, you’d be awfully limited. There are thousands of yidams, wildly different, vividly specific. You can experience becoming several, in order to develop and master their particular capacities, stances, and activities. You can be an enlightened necrophiliac witch, for instance. That’s a quite different style of beneficent action, effective in a diffent set of circumstances, for different purposes.

Now you are thinking:

This is extremely silly. No one is a god emperor, and no ritual can make you that.

What it can do, when it works, is to explode your sense of fixed self, and reveal previously unimagined possibilities for how you can be.

These are not superhero fantasies—that is not at all how yidam practice functions—but attitudes and modes of interaction that you can realistically adopt. These may grant significantly greater power and skill in your work to benefit all beings.

Since you are no longer limited by your self, you spontaneously act with unpremeditated nobility.

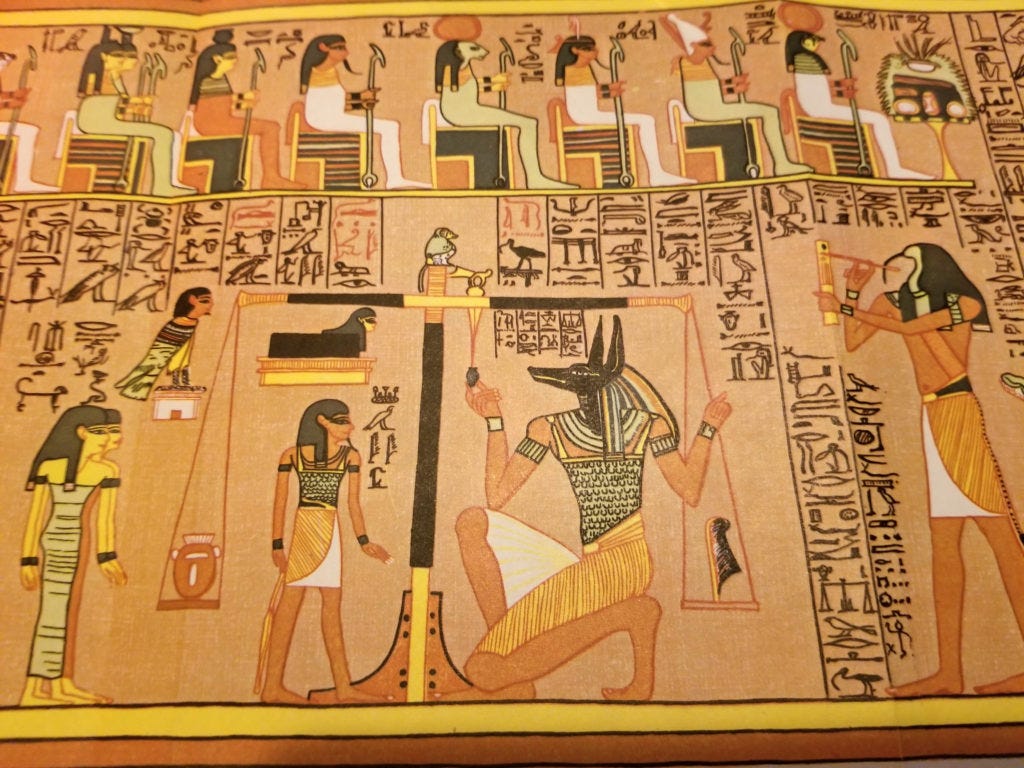

Weighing the heart of the dead

Some mistaken metaphysical axioms:

All disparate goods can be aggregated into The Good.

The Good is specifically morally good.

Therefore, individual people are objectively and quantitatively morally good or bad overall.

These falsehoods were promulgated by Ancient Greek philosophers, who are the direct cause of most of what is wrong with the world. However, they are much older. The Egyptian priesthood, from whom the Greeks got half their bad ideas, claimed that when you die, your immortal soul gets weighed for purity from sin, and your afterlife fate depends on the tipping of the balance. Aggregate goodness is one of the many misleading myths we get via both the Greeks and Christianity from still more ancient sources.

In 1988, as a graduate student, I bought a used 1978 Volkswagen Rabbit so I could drive from Cambridge to Amherst to see my girlfriend. It was, in most respects, a terrible car, rusting out and falling apart. I spent many full-time days disassembling it and replacing bits. As an alternative, I might have considered the Ferrari 308GTS a better car of the same era. However, for my purposes, the Rabbit was far superior, because I could afford it. A Ferrari was a useless abstraction.

It’s another mistaken metaphysical axiom that value must be either objective (the main line of Western thought) or subjective (Romanticism, existentialism, postmodernism, and nihilism). Value is not objective: it depends on context and purposes. It is also not subjective. Less expensive cars are better. More reliable cars are better. Faster cars are better. Safer cars are better. Less polluting cars are better.

There is no way of adding up criteria into an overall “betterness” rating. Better for what?

Some people are better than others at playing the accordion, or fixing rusty engines, or solving differential equations. Excellence at any of these deserves plaudits. They don’t make one person overall better than another.

(On the other hand, aggressively refusing to be good at anything, or to acknowledge that someone makes better blueberry muffins than you can, does make you worse than normal people…)

You should be less ethical

This is one of my favorite slogans, for its shock value.

I mean it in a particular way. Not that you should be unethical, at all. (You should be a bodhisatva. That is highly ethical.)

I mean that you should restrict ethical reasoning and moral judgement to their proper subject matters. There are many kinds of value other than moral value: for example religious value and aesthetic value. Already in Nietzsche’s time, types of value were collapsing together. God died, so religious value is mostly no longer taken seriously. The elite consensus about “great art” broke, so there are no longer any standards of what is good or bad aesthetically. Mostly, everyone has agreed not to argue about these things.

We have not agreed not to argue about ethics. Therefore, if you want to argue that something is good or bad, you need to argue that it is morally good or bad. So you don’t say a movie is just generally mediocre, you say that it’s morally unacceptable.

This metastasis of morality is dysfunctional, and it enables the culture war. You should be less ethical—in your opinions about how people dress or what words they use or about today’s celebrity-having-sex-with-the-wrong-sort-of-person scandal.

There is also, however, a more serious issue: How ethical should I be?

This is, for most people, the main question about ethics. It comes up several times a day for most people, I suspect. We know what’s right and wrong—that’s rarely an actual problem for adults—but:

How do I know if I’m morally adequate? Do I really have to be ethical about this trivial matter? Am I being too ethical, more scrupulous about it than normal people? How much can I legitimately get away with here? But maybe that thing I did yesterday was really kind of bad, so I should be extra moral today to make up for it?

There is no existing ethical framework in which these questions can even be asked, much less answered. That’s a serious problem.

In the current pop “master or slave morality” debate, this seems to be the underlying, motivating concern. Both sides apparently understand “master morality” as I don’t intend to be ethical unless I feel like it, and “slave morality” as You have to be maximally ethical at all times, so I can feel safe. These are both childish.

They’re a somewhat natural misunderstanding, though, because Nietzsche’s opposition of master morality to slave morality was a mis-framing. The aristocratic Greek ideal is mostly not about morality at all. It’s about aretē, “excellence.” Due to the collapsing-together of value types (already begun by Aristotle) aretē eventually got assimilated and reduced to morality.

Excellence in muffin making is not a moral matter. The aristocratic ethos—not morality—celebrates excellence of all sorts, and the (supposed) slave ethos rejects them all.

The Tibetan Caesar with the wakeness-mind of Buddha

Nietzsche described the Übermensch, “Superman,” as the semi-divine future human who would unify the master and slave moralities. Or something. His discussion is contradictory, vague, and trails off into madness at this point. At times, it seems that the Übermensch is a ruthless, amoral horseback barbarian warlord. This appeals to many historical (Nazi) and contemporary (alt-) advocates of the far right. It appears repulsive and insane to most people (including me).

Another formulation Nietzsche gave was “The Roman Caesar with the soul of Christ.” What does this mean? I don’t think he knew. He was groping for a synthesis, but couldn’t quite reach it.

In Vajrayana, however, we have one extensive answer available.

Gesar of Ling, the legendary Tibetan ruler, warrior, and spiritual leader, is the central hero of a vast collection of stories that has been described as the world’s largest epic tradition. In European terms, we could say that Gesar is both King Arthur and Merlin. Like Arthur, he is the exemplary king and warrior who unites and defends his people in times of trouble and great danger. Like Merlin, he is a spiritual leader, but also a magician and trickster. In later centuries, he is also seen as a full-fledged tantric deity and important figure of the Dzogchen tradition.4

“Gesar” is the Tibetan mispronunciation of “Caesar.”

The Gesar epic tells how the king, an enlightened warrior, in order to defend Tibet and the Buddhist religion from the attacks of surrounding demon kings, conquers his enemies one by one in a series of adventures and campaigns that take him all over the Eastern world. He is assisted in his adventures by a cast of heroes and magical characters who include the major deities of Tibetan Buddhism as well as the native religion of Tibet. Gesar fulfills the Silk Route ideal of a king by being both a warrior and a magician. As a magician he combines the powers of an enlightened Buddhist master with those of a shamanic sorcerer.

As a Buddhist teaching story, the example of King Gesar is also understood as a spiritual allegory. The "enemies" in the stories represent the emotional and psychological challenges that turn people's minds toward greed, aggression, and envy. The teaching is that genuine warriors are not aggressive, but that they subjugate negative emotions in order to put the concerns of others before their own. The ideal of warriorship that Gesar represents is that of a person who, by facing personal challenges with gentleness and intelligence, can attain spiritual realization.5

Gesar is a preeminent yidam in the particular Vajrayana systems I’ve participated in. He was championed particularly by Ju Mipham, a key recent historical antecedent of those systems, and author of the root text for my book Meaningness. Years ago, I wrote:

Mipham and Nietzsche wrote their major works around the same time in the late 1800s. Their life stories and works are parallel in fascinating ways. They both wrote abstruse academic philosophy and they both wrote wild, prophetic, heterodox quasi-religious allegories. I wish I could introduce them to each other.

Scott overcomes rationalism to get it right

Rationality is good. Reasoning is good. Logic is good. Scott is excellent at reasoning. In his last section, he glumly concedes that it has failed him in this case: “I have no real answer to this question.”

Rationalism is the overvaluation of reasoning, particularly relative to observation. Logic cannot help you if your axioms are false. Scott unthinkingly accepts one: that ethics must have an ultimate foundation, from which all the specifics can be derived rationally. His preceding sentence:

At some point altruism has to bottom out in something other than altruism. Otherwise it’s all a Ponzi scheme, just people saving meaningless lives for no reason until the last life is saved and it all collapses.

This is ethical eternalism, one of the fundamental wrong metaphysical commitments of the Western tradition. Christianity said that morality bottoms out in God’s commandments, but he died. Rationalism tried to ground ethics in logical certainty, but failed.

There can be no foundation for ethics, but that is not a problem. None is needed because moral reasoning is not, and should not be, the main cause for moral action.

You can get a real answer through non-conceptual observation of concrete interactions, setting aside reasoning from hallucinatory metaphysics. (Technically, this is called “ethnomethodology” or “opening awareness.”)

Right after “I have no answer,” Scott observes himself playing Civilization IV, and immediately gets the right answer—the same groundless answer Vajrayana gives:

I want to be happy so I can be strong. I want to be strong so I can be helpful. I want to be helpful because it makes me happy.

I want to help other people in order to exalt and glorify civilization. I want to exalt and glorify civilization so it can make people happy. I want them to be happy so they can be strong. I want them to be strong so they can exalt and glorify civilization. I want to exalt and glorify civilization in order to help other people.

I want to create great art to make other people happy. I want them to be happy so they can be strong. I want them to be strong so they can exalt and glorify civilization. I want to exalt and glorify civilization so it can create more great art.

Edited for concision and clarity.

All this is from Scott’s summary of Yglesias’ position. He doesn’t link specific posts, so I haven’t checked whether it’s accurate.

This quote, from Marianne Williamson, is often misattributed to Nelson Mandela. I am not generally a fan of Williamson, but I think she nailed this one. I wrote something similar in “Drinking the Sun.”

From Geoffrey Samuel’s “From Folk Hero to Deity,” a review of The Epic Of Gesar Of Ling.

This post was so fun to read.

My forever questions: who, in any tradition, is practicing being awesome at relationships? At giving and receiving love? At resolving misunderstandings? Transforming conflict?

I appreciate art, medicine and a really well-designed logistical plan, but these other topics matter to me so much more. And I think it’s what at least a significant chunk of people are really asking about when they ask about morality.

Recently in a recorded conversation with Charlie, you spoke about man in an elevator who whose companion was annoyed with him. This man was able to transform the conversation in some way that both made his partner feel heard, but also dissolved the frustration of the situation. Who is the best at this? Who is even quite good at it, enough to offer instruction?

The absence of aspirational examples seems to be part of the reason why people get so upset when “so-and-so person I admired had sex with the wrong person.” People are looking for role models who are awesome at navigating relationships when the stakes are high, like when sex or anger are in the mix. They project their desire for a heroic example onto all manner of targets. And I get it—I can’t think even think of an imaginary ideal like Achilles or Merlin, but for interpersonal heroism. We have so many examples of heroes who are smart, hot, rich, enlightened, powerful, interesting, agile, fearless, the very best at violence—who is the very best at mediating conflict so no party feels humiliated? Where is our warrior class of citizens who knows how to diffuse a bar fight before punches are thrown?

I don’t want to “face personal challenges with gentleness and intelligence to attain spiritual realization.” Facing personal challenges with gentleness and intelligence seems fully self-justifying! I would prefer to practice that directly.

There is so much be gained, in so many different domains of human activity, by valuing expertise in these areas. Where are the people being heroic and awesome *like this*?

My e-mail program apparently broke and I first received an e-mail from you simply with the subject „You should be a God-Emperor“ and no content.

That was disorienting and refreshing.