In this issue:

I’m writing the meta-rationality part of the meta-rationality book

Do you want to read my drafts?

Here’s the first chapter, want it or not!

The meta-rationality part of the meta-rationality book

My meta-rationality book (“In the cells of the eggplant”) has five Parts, but doesn’t discuss meta-rationality until Part Four! I’m working on that Part now. “Getcha boots on” was an outtake from it.

Parts One and Two, about rationalism and reasonableness, are essentially complete and available on the web. Part Three explains how rationality actually works, which is a prerequisite to explaining how meta-rationality works. It has a long summary on the web. I can’t write a finished version until I know exactly how Part Four will depend on it.

So my plan is to write Part Four, and then Part Three, and then release those four Parts as individual paperbacks/Kindle editions. Together they’ll add up to roughly six hundred pages. A while later, I’ll put them on the web for free.

Previews here on Substack

I will post drafts of sections here as I finish them. Many will be paid posts: as a thank you to paying subscribers, and also to get feedback particularly from those enthusiastic readers who wish to contribute and be involved in the book’s creation.

I’ll also post occasionally about meaningness, Vajrayana Buddhism, and vampires; but meta-rationality will be my main focus this year. Maybe you don’t care about that! It may be a post per week for several months. Is that too much?

Substack has a “sections” feature that allows subscribers to choose a subset of posts they want to see—you could skip meta-rationality and subscribe to the “section” just for vampires, for example. Would you want that?

Want it or not, here is a draft of the introduction to Part Four. It’s all free, this time!

Part Four: Taking meta-rationality seriously

This is a book about meta-rationality; yet its first three Parts discussed the topic only vaguely and in passing. Those Parts explained conceptual prerequisites instead, which took several hundred pages.

Finally, Part Four is about meta-rationality!

The essence of meta-rationality is actually caring for the concrete situation, including all its context, complexity, and nebulosity, with its purposes, participants, and paraphernalia.

“Well of course I care! What do you mean, ‘actually’?”

I mean caring more for the situation than about abstractions. “Actually” caring, as opposed to:

Caring more about your identity, role, and incentives than for the situation. A key example is wanting the comforting feeling of expert competence and control that you get from doing being rational, more than you want to engage with the situation in all its uncontrolled mess. Relatedly: wanting the institutional rewards that come from being seen to follow rational rules, more than caring whether or not doing so helps.

Caring more about representations of the situation than for the situation itself. Some examples: relying on others’ summary reports on it; prioritizing abstract theories over concrete specifics; detached creation of new theories; optimizing artificial metrics of situational goodness.

The earlier Parts may have given the impression that meta-rationality is a handful of rules-of-thumb that sometimes improve the working of rationality. That’s not entirely wrong; and since this is a book about technical work, intended for readers who do technical work, we’ll emphasize that use of meta-rationality.

However, it misses the overall point. The question meta-rationality always asks is:

What does this situation need?

The answer may involve improved rationality. It may involve deeper, wilder, more moving myths. It may involve prioritizing reasonableness over rational rules. It may involve an angle grinder, a proclamation, or a line dance.

Whether rationality is relevant, whether it can supply the right tools for the job, is a meta-rational concern.

Meta-rationality answers its fundamental question by engaging with the play of the situation, while orienting to the broad context and to the purposes of participants and potential participants.

There may also be no apparent answer—and you remain engaged anyway. If rationality is your default mode, when it isn’t working it’s tempting to disengage and play a video game instead. Meta-rationality builds emotional trust that situations are workable even when there is no obvious way forward.

The subtitle of this Part is “Taking meta-rationality seriously.” Taking it seriously means asking its question and acting on its answers.

It means relativizing the value of rationality, regarding it as a collection of sometimes-useful tools, not as The Cosmically True Way.

It means developing explicit and implicit practical and theoretical understanding of how and when and why reasonableness, circumrationality, rationality, and meta-rationality work. It means reflecting on the activities they recommend, in order to choose how to reason and act deliberately, rather than falling into mindless implicit defaults.

We pause the draft to bring you this message:

The introduction is often the most difficult part of any text to write. It’s usually best to leave it for last; then you know exactly what needs to be introduced.

The text above is the introduction to the introduction of Part Four. (The rest of the introduction follows below this block.) I was able to write it quite easily, but only on the basis of recent discussion with my spouse Charlie Awbery, who significantly clarified my understanding of meta-rationality. Whereas I approach the topic from decades of experience in technical work, Charlie’s basis is decades of facilitating people moving up the “J-curve of adult development,” discussed later in this post.

Rational workers—STEM professionals, entrepreneurs, and executives—are Charlie’s typical clients. When we get stuck, it is usually either because we’re failing to be rational about problems in some domain (most often relationship), or because we’re stubbornly insisting on treating a domain of work rationally, when meta-rationality is called for. Charlie gets you unstuck by intervening in emotionally fixed, habitual thought and action patterns, drawing on understandings from Vajrayana and from adult developmental psychology.

Prerequisites, review, and caveats

How did you get here?

Parts One, Two, and Three built up layers of concepts that help make Part Four make sense. It would be best to read them first. However, in a book about meta-rationality, you may be impatient to get to the point. You may choose to skip the hundreds of pages of preliminaries, and read Part Four—or even Five—first.

In the web version, non-standard terms appear with a dotted underline; clicking on those pops up a definition, with a web link to a full discussion. In all versions, the Glossary includes definitions for such terms. Reading it could be a way to get a rough understanding without wading through earlier Parts.

Conceptual understanding is not the only prerequisite, however. Prerequisites of experience and emotion are as important.

Basic rationality operates in the comfortable domain in which formal methods work reliably, and it is obvious which ones to use to Solve any Problem. (I capitalize Problem and Solution to indicate that these are formal objects, not real-life troubles and repairs.) Advanced rationality is willing to tackle Problems for which a Solution method is not obvious, no method may yet exist, and for which there may or may not even be a Solution. Adventure rationality goes a step further, addressing situations in which there isn’t yet even a clear Problem.

Experience with advanced rationality is probably necessary to make sense of meta-rationality; and some acquaintance with adventure rationality will help a lot. If you are not comfortable working in the absence of any specified or guaranteed method, this Part may be intellectually interesting, but probably not yet useful in practice.

Meta-rationality, in contrast with rationality, squarely confronts nebulosity: the inherent squishiness of everything in the eggplant-sized world. Nebulosity is the reason rationality of any kind can’t work unaided, and often can’t work at all. The certainty, control, and understanding rationalism promises are simply impossible. This can be emotionally hard to accept, and recognizing it can precipitate a nihilistic crisis. Understanding how and when and why rationality often does work, despite nebulosity, is the antidote.

Crisis or no crisis, a prerequisite to even trying to understand meta-rationality is a recognition that rationality can’t overcome nebulosity, and therefore some other approach is often required.

On the other hand, even if this Part doesn’t connect with your experience, you may find it fascinating conceptually. If you keep it in the back of your mind, in time you may find bits of the story suddenly making sense of specific troubles and successes in your rational work. And, the explanation as a whole may become useful in retrospect in a few years. Then you may want to reread the book. It will make a different, more powerful kind of sense once you have the experiential prerequisites.

Parts One, Two, and Three: what you may have missed

The short chapter “Rationality, rationalism, and alternatives” in Part One provides definitions of key terms: rationality, rationalism, reasonableness, meta-rationality, and meta-rationalism. Even if you read that before, it was hundreds of pages ago, and it might be useful to review it now.

Part One explained why rationalism is a wrong theory of how rationality works. Rationalism can’t deliver on its promises, because they depend on an absence of nebulosity, which is pervasive. It has no credible explanation of how formal reasoning connects with the world, implicitly relying on metaphysical “correspondence fairies.”

Part Two explained how reasonable activity connects perception, thought, and action, which bare rationality cannot do.

Part Three explained how rationality works, with a “floorplan” or “wiring diagram” that we’ll make frequent use of in Part Four. This explanation is quite different from the rationalist one. You probably took that one for granted, because it is transmitted implicitly in STEM education. A more accurate explanation is required to understand meta-rationality; we’ll review it briefly in the next chapter. One key aspect is the way circumrationality, a modified form of reasonableness, connects rationality with the world.

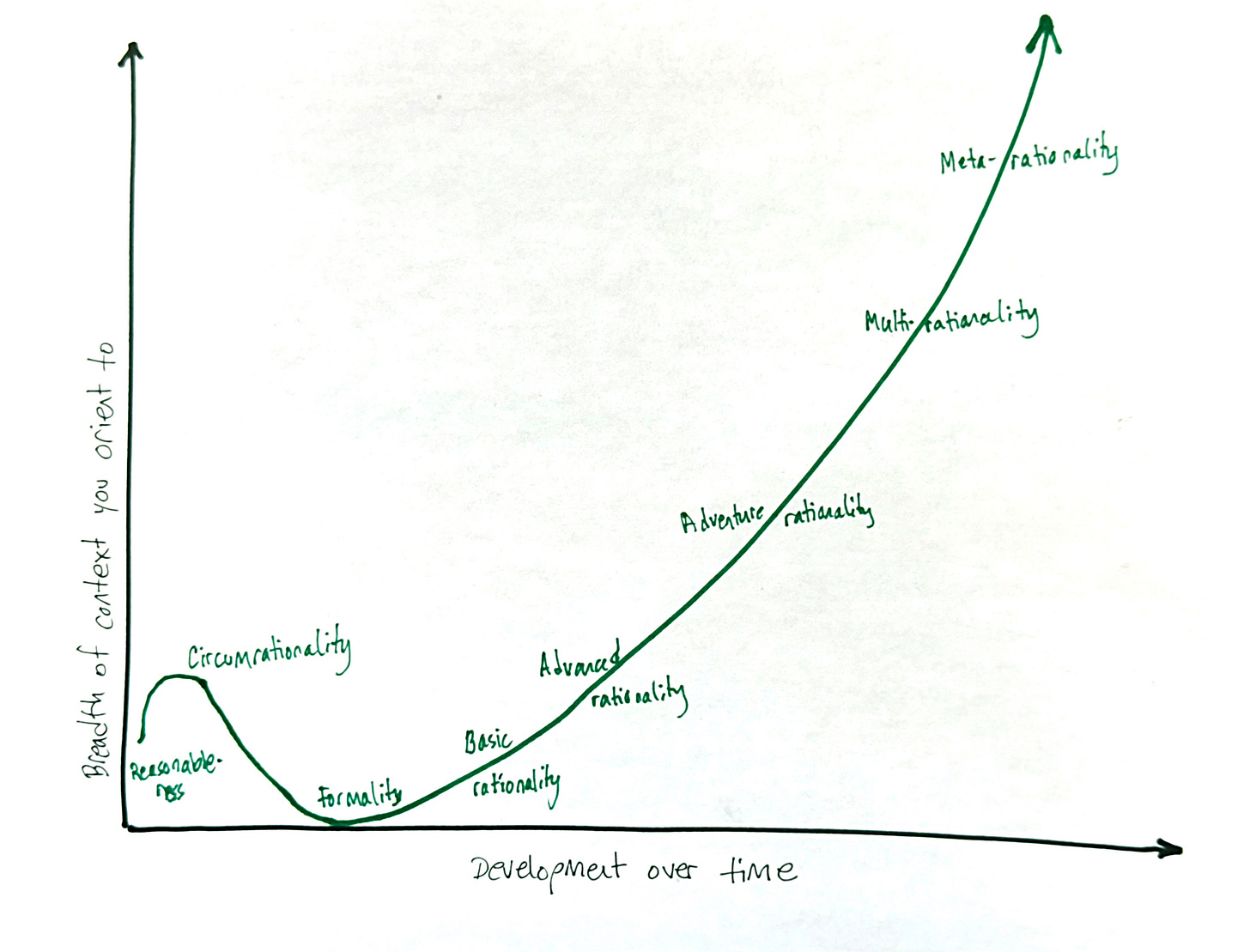

The J-curve of increasingly sophisticated modes of reasoning, introduced in Part Three, summarizes concepts key throughout the book, and in Part Four particularly. We’ll return to the J-curve toward the end of this Part, with a practical discussion of how to move up it yourself. For now, a compact presentation of waypoints on the path:

Reasonableness: outside and oblivious to rational systems. Appropriate in, for example, routine housework, everyday social interaction, and “unskilled” labor.

Circumrationality: working at the edge of a rational system, most of which you can’t see, don’t understand, or temporarily ignore; passing stuff back and forth across its boundary. Typical in semi-skilled office work, and the mode of skilled technicians as well.

Formal problem-solving: application of formal methods to a formal Problem that has no specific connection with reality. Most STEM education before graduate school is this.

Basic rationality: application of obviously-relevant formal methods to a Problem that is known to have a Solution, and that connects to a specific part of reality via circumrational practices that you explicitly ignore; reasoning entirely within a single system. Most paid rational work is this, until you reach relatively senior levels.

Advanced rationality: selection or creation of formal methods to a Problem not definitely known to have a Solution, and for which it is not clear what methods may work. The domain of technical “wizards”; senior technical work.

Adventure rationality: application of rational methods to a mess in which it is not clear what the trouble or opportunity is, with the aim of locating, formalizing, and Solving a Problem. Genuine scientific research; exploratory engineering and design studies; organizational innovation, as in entrepreneurship for example.

Multi-rationality: bringing initially unspecified, potentially multiple, potentially contradictory whole rational systems to bear, typically on a mess or semi-specified problem. The “wisdom” of unusually creative, insightful senior professionals.

Meta-rationality: effective activity that may or may not draw on elements of rational systems, as one among many sorts of resources, without privileging their status; abandoning the framing of “self facing a situation that should be turned into a Problem to Solve”; a panoramic view outside and above systems and the contexts within which they operate, simultaneous with a detailed awareness of situational specifics. As a regularly practiced mode, most often found in research lab leaders, engineers turned group leaders, and senior executives. However, anyone who uses technical rationality must make meta-rational choices, even if only as unthought defaults.

Part Three left off at adventure rationality, noting that it shades toward meta-rationality. This Part picks up the thread at adventure rationality, with the next chapter explaining multi-rationality in contrast with it. Overall, Part Four continues to ascend the J-curve, getting deeper into meta-rationality proper as the text progresses.

Meta-rationalism

This whole book is an expression of meta-rationalism. Meta-rationalism is an explanation of how and when and why reasonableness, rationality, and meta-rationality work. That makes it loosely parallel to rationalism, a different explanation of rationality.

The biggest practical difference is that according to rationalism, rationality always works, and you should always use it; whereas, according to meta-rationalism, rationality only sometimes works, and never without circumrational support. You should use it only when appropriate, which depends on contexts and purposes.

Another difference is that rationalism’s explanation is completely false, couldn’t work even in principle, and is often catastrophically misleading for practice; whereas meta-rationalism’s explanation seems roughly right.

More subtly, they are different types of explanation. Rationalism tries to be a rational theory of rationality, whereas meta-rationalism is a meta-rational understanding of multiple modes of reasoning and activity. We’ll cover the distinction between “theories” and “understandings” in “Meta-rational epistemology,” a couple of chapters after this one.

Meta-rationalism is valuable in practice for its understanding of how and when and why the different modes work or fail. That lets you choose more accurately how and when and why to use them. It’s also a prerequisite to improving their operation.

Several easy misunderstandings, easily dispelled

This section is a bit theoretical, verging even on philosophical, and you can skip ahead if you like.

Rationalism lumps all non-rational modes as “irrational.” Meta-rationality is non-rational, but is quite unlike both irrationality and various other non-rational modes.

Irrationality means failure or refusal to think well, or act effectively, when you should. It means “unreasonable” or “nonsensical,” or “stupid” or “crazy,” in the non-clinical sense of those words. By this definition, irrationality is contrary to all the modes on the J-curve, each of which generally works well in many situations. In particular, meta-rationality is not irrational, because it can sometimes produce breakthrough results, and rarely makes things worse.

Anti-rationalism means any articulated ideological rejection of rationality, in contrast with irrationality’s ignorant or emotionally stubborn rejection of it. Ironically, anti-rationalism is often structured as a rational system, and may deploy rational arguments against rationality—typically in overreaction to the errors of rationalism. Meta-rationality values rationality highly and does not reject it, so it is not anti-rational.

Reasonableness is one sort of effective informal activity (and therefore not formally rational). Reasonableness, unlike meta-rationality, does not orient to systematic rationality at all.

Circumrationality, like meta-rationality, uses informal means to relate rationality with the world. However, circumrationality relates only its immediate situation with a small part of a single rational system, most of which it treats as irrrelevant. Meta-rationality maintains an overview of a broad context that may include zero, one, or many rational systems. Circumrationality treats the system as a fixed given; metarationality takes systems as inherently fluid and alterable.

“Meta-rationality” is a quite misleading term, for multiple reasons. (Unfortunately, neither I nor anyone else has yet found a better alternative.)

Meta-rationality is not a special type of rationality. It can’t be, because it often operates prior to, or outside of, any definite ontology. It takes rational methods and ontologies as contingent objects, whereas rationality takes them as the subject; as constitutive givens.

“Meta-rationality” suggests the application of rationality to itself. That is, in fact, the project of rationalism, not meta-rationality. Meta-rationality is not a rational system. Reasoning about how best to apply rationality cannot be formally rational, due to the nebulosity of whatever you are applying it to.

Further, after the move from multi-rationality to meta-rationality, rationality is no longer particularly central. It’s just one factor in the context, along with everything else.

Meta-rationality isn’t a rational or general theory of metaness, nor does it rely on any particular idea about what “meta” means.

“Meta-rationalism” suggests an ideology, an -ism. Rationalism is an ideology: it makes sweeping, absolutist normative claims, based on groundless, a priori metaphysical certainties. Applied in politics and economics, it has led to large-scale atrocities and disasters. Meta-rationalism might in principle get misused similarly, but its claims are far more modest, nebulous, and based in commonsense observations of material reality. Its norms—discussed in the next chapter—are rules of thumb, not absolute demands.

In understanding meta-rationality, we need to avoid two extremes: anti-rational Romantic intuitionism, and premature rationalist formalization.

Meta-rationality might be described as “intuitive” or “creative.” In fact, across diverse literatures, nearly all the discussions I have found use both those words. I avoid them, because they are thought-stopping clichés.

What does someone mean when they say an idea is “intuitive”? They mean “I don’t know why I believe that, so don’t ask.” Likewise, “creative” means “it’s new, and don’t ask how someone came up with it, because you won’t get an answer.”

When challenged, people who like these terms resort to Romantic monism: everyone is mystically connected to the Source, which is really The Entire Universe, but not everyone is aware that they are Actually God. Special souls tap into the Source by Looking Deeply Within to find Cosmic Truth, and that’s how intuition and creativity work.

This is unhelpful.

Much of what we do in meta-rationality—and in fact in all aspects of life—is poorly understood. To the extent we do understand it, it’s difficult to articulate. Understanding it better, and explaining as clearly and accurately as we can, is often valuable. Meta-rationality is less understood than some other ways of being, because it is rare and almost entirely unstudied. Nevertheless, it involves a diversity of specific phenomena which we can partly describe straightforwardly, in non-mystical terms. This Part does just that.

The opposite fault to Romantic intuitionism is to try to make a fully rational theory of meta-rationality. For example, some authors suggest that “analogy,” understood as something like mathematical homomorphism, is the whole story.

This is a premature formalization, covered in Part Three as a typical rationalist failure mode. It grabs the simplest, most ready-to-hand ontology available, and holds onto it in a desperate attempt to avoid confronting the nebulosity of the phenomenon: which is meta-rationality in this case.

Premature formalization is also a panicked attempt to avoid confronting lack of confidence in one’s own ability to feel for a more accurate ontology. That lack of confidence is usually accurate in cases of premature formalization. Before attempting a new explanation of meta-rationality, one should have developed this capacity, which is itself a key aspect of meta-rationality. It’s covered in the upcoming chapter “Getting an ontology.”

An accurate ontology of meta-rationality—an explanation of its basic nature, its parts and their relationships—is much more complex than a simplistic model of analogy. This Part includes my attempt at one.

I would love to hear what you think!

A main reason for posting drafts here is to get suggestions for improvement from interested readers.

I would welcome comments at any level of detail: from typos, to improvements in sentence, paragraph, and section-level flow, to better explanations, to overall structural problems.

What is unclear?

What seems wrong, or that you’d at least need more explanation or evidence to believe? (Bearing in mind that this is an introduction only.)

How could I make it more relevant? More practical? More interesting? More fun?

Where else might a diagram help?

If you ask "Do you want me to post drafts and notes about X topic?" my answer will be "yes". If instead of a yes/no question, you were to ask a mutiple-choice question about which of your topics on which I'm most eager to see your unpublished notes and drafts, it would be the follow-up essays on stage theory. You alluded to these unpublished notes at the end of your essay about Misunderstanding Stage Theory. https://meaningness.com/misunderstanding-stage-theory

I'm pretty sure they are supportive of parts 3 and 4 of In The Cells Of The Eggplant, if not quite belonging there.

You listed them as follows:

"- How to use adult stage theory: is this good for anything?

- Lag: what is a stage, anyway? remodeling the ontology

- The circumrational shantytown: the dire social and cultural effects of stranding half our population at stage 3.5 by requiring semi-systematicity for employment

- The landscape between stages 4 and 5: landmarks in the trackless territory

- The past, present, and future of stage theory as science: where did this stuff come from, and why should I believe any of it?"

I’m happy to see that you’ve resumed work on *In The Cells of the Eggplant* and, even better, getting to the heart of the book.

This introduction seems a bit repetitive, though, for someone who has read the previous chapters? You’re addressing someone who skipped the previous chapters and telling them, again, what they need to know. But wouldn’t someone who wants to skip ahead skip this part too?

Since this is a new blog, maybe a recap is appropriate here, but as part of the book, I think it’s better to trust that someone who skipped ahead too far will go back if they’re feeling confused.