Seeing and doing mythically

How we find the foundational self-possibilities that rationality cannot provide

In Meta-rationality, I describe three modes of thinking, feeling, seeing, and acting: reasonableness, rationality, and meta-rationality. This post is about another, which I’ll call the mythic mode.

This is the mode not just of myths—but of dreams, visions, storytelling, and make-believe play.

It is the mode of strange recurring fantasies, of compelling mental images, and of sudden recognitions of intense but inexplicable meaningfulness in the actual world.

It is the mode of ecstatic ritual, of encounters with gods and demons, and of falling in love with someone you barely know.

The mythic mode is foundational for the others. They build on it, and they don’t work well without its inspiration.

The mythic mode supplies purpose, a critical ingredient, for all the other modes. Reasonableness can see only mundane, conventional purposes, which are ultimately unsatisfying. Rationality only works by excluding consideration of purposes. They have to be supplied externally, and as sterile abstract formalisms. Meta-rationality reflects on purposes, but relies on the mythic mode for their inspiration.

The mythic is also the easiest mode from which to access the complete stance. That is the accurate and enjoyable way of engaging with meaning and meaninglessness. The mythic mode, like the complete stance, plays with pattern and nebulosity, boundaries and connections.

I’ll explain these functions in future posts. They will relate the mythic mode with the many seemingly disparate topics I discuss, thereby making the connections among them clearer.

But the mythic mode is also vital, in its own right, for all of us. It is an essential part of what it is to be human, at every stage in life.

What the mythic mode is like

Most of what’s written about the mythic mode attempts to explain how it works. I’ve read a ton of theories, in psychology, history, anthropology, religion, and folklore studies. After all that, I don’t understand it very well, and I suspect no one else does either. The little I have understood intellectually doesn’t seem greatly useful in practice.

Fortunately, though, the mythic mode is a universal experience, so everyone understands it intuitively. Rather than “how it works,” we can ask what it is like. I will point to some characteristics, so you know what I mean when I say “mythic mode.” That might also help you access the mode if you want to but it seems difficult. And, these features are inherently fascinating!

The mythic mode is usually described in terms of thinking and feeling: mental stuff. Depth psychology, particularly the work of Carl Jung, dominates popular conceptual understanding of the mode. Although that’s valuable, it’s also distorting. Thinking and feeling are aspects of all the modes, but so are perception and action—and they are at least as important. The mythic mode is just as concerned with seeing and doing as is the reasonable one. That goes triple for the rational mode, in which perception and action are mere theoretical afterthoughts!

The mythic mode develops in middle childhood, preceding the others. Children relate to the world “mythically” before they can be consistently reasonable—let alone rational. We all continue to employ the mythic mode throughout life; but keeping its childhood origin in mind may help make sense of the descriptions that follow.

Seeing and acting two ways at once

Fundamentally, the mythic mode involves seeing and acting in a situation in two ways simultaneously. One way is relatively mundane and literal; the other less so. We coordinate their seemingly discordant meanings so that each enhances the other. Through experience, we gain skill in relating them, so that acting on mythic meanings creates good mundane outcomes; and better understanding of the mundane deepens the experience of the mythic.

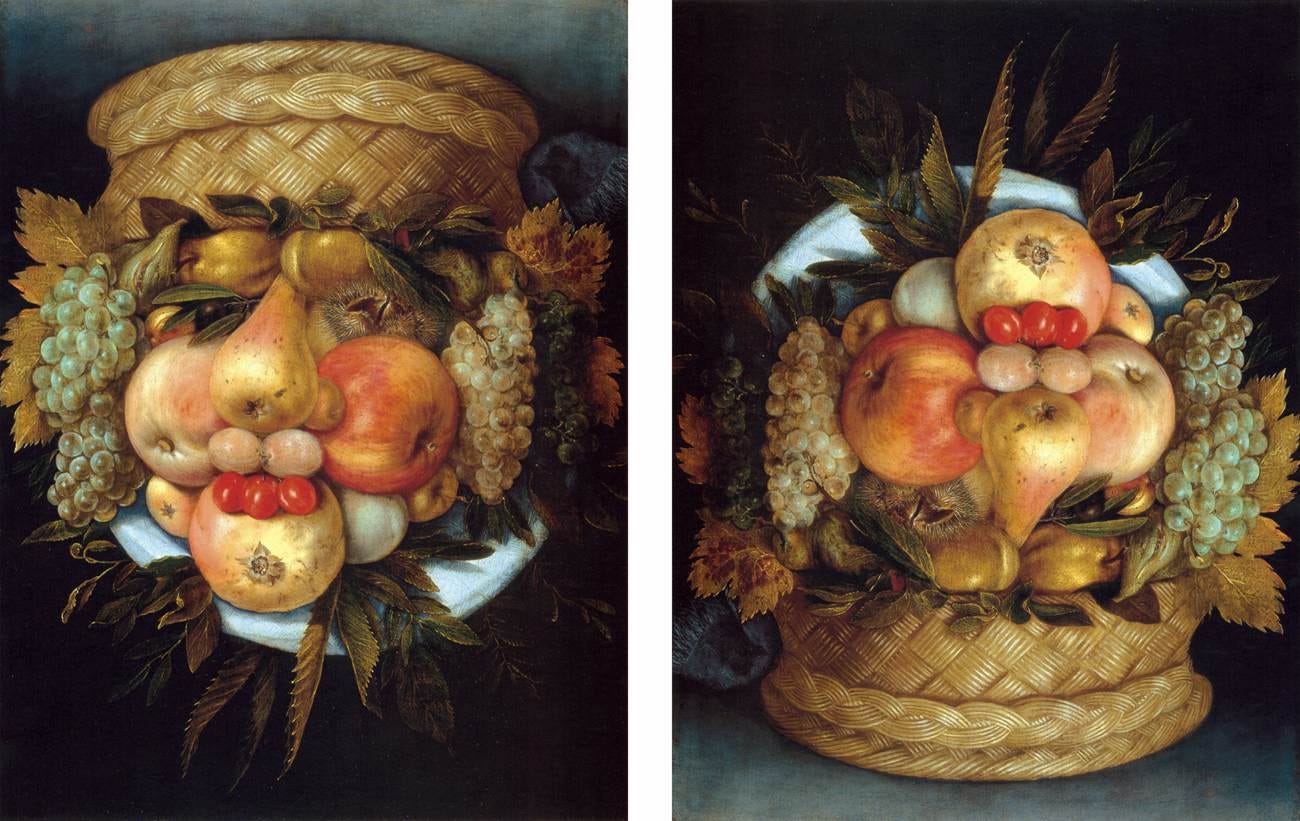

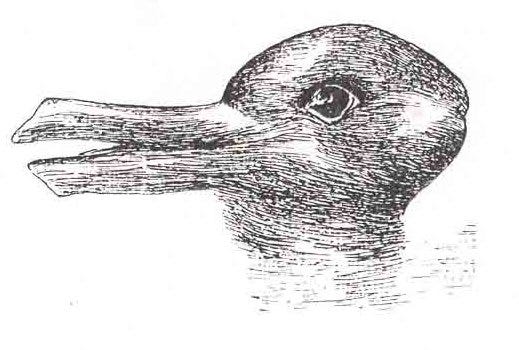

The mythic mode requires dual vision, somewhat metaphorically speaking. Ambiguous images are analogous. We can see the picture either as an ugly dude, or as a plate of fruit. As a duck, or as a rabbit.1 Once we’ve seen it both ways, we’re aware that both are interpretations of meaning. They are both valid, although radically different.

Children’s play constantly relies on this dual vision. A fork becomes a spaceship, and the child zooms it around the room, seeing it as a spaceship, acting on it as a spaceship. At the same time, the child remains perfectly aware that it is a fork—and sees it, and holds it, also as a fork.

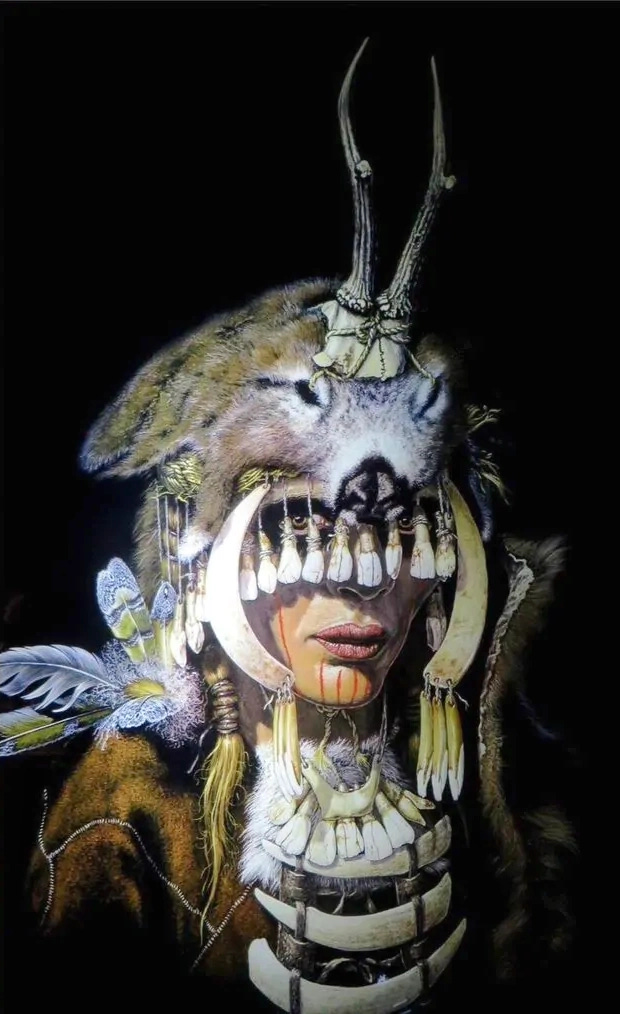

In ritual, a shaman becomes a bear-goddess, and as a ritual participant you see her as a bear-goddess, and act toward her as one, even while remaining perfectly aware that she’s your aunt.

The mythic mode not only tolerates, but actively enjoys, contradiction as well as ambiguity. You can’t pick up a spaceship; you are picking one up, and it’s also a fork, and this isn’t a problem.

Reasonableness is not comfortable with contradictions, and will try to change the subject, or obfuscate when they can’t be avoided. Rationalism, of course, rejects contradictions outright. It is founded on the Law of the Excluded Middle. “It will not be possible to be and not to be the same thing,” is one way Aristotle put it. Rationalism insists that every possible proposition is either absolutely true or absolutely false—in the face of constant evidence that nearly all of them are neither. It is only at the stage of meta-rationality that we regain skill in juggling contradictions—and delight in them.

Binary conceptual opposites, and their middles or paradoxical exceptions, fascinate the mythic mode. That which is neither alive nor dead, but somewhere between; someone who is both a human and a goddess, or both a human and a bear; entities that are simultaneously invisible and seen.

Children’s stories, and myths and dreams and visions, feature impossible transformations, across conceptual boundaries, of places, people, things, activities. Frequently they shift the apparent ordinary into the imaginary extraordinary, the boring into the bizarre—and then sometimes back again. These evoke wonder, curiosity, delight, and sometimes amusement or horror.

Ovid’s Metamorphoses is about shape-changing transformations. It is the largest and most influential collection of Greek and Roman myths. According to Ovid, Adonis (the hottest guy in history) was the son of beautiful princess Myrrha. She seduced her own father, the king, who thereby became Adonis’ father. For this sin of incest, Myrrha was transformed into a myrrh tree while pregnant. When her gestation (as a tree) completed, she gave birth to a human son, Adonis. As you can see, above! (Mythologists explain how this all made sense in the context of Ancient Greek understandings of sex and gender, but I have my doubts.)

As in this tale, many mythic transformations are not discrete, definite changes from one thing into another; the transformed entity remains both. Myrrha is both a tree and remains a human mother. In children’s make-believe, a sofa becomes a pirate ship and remains a sofa. In a dream, I am back in high school, anxious about the algebra exam I forgot to study for, but recall also that I have several university STEM degrees—and wonder why I am there. In the mythic mode, “to be and not to be the same thing” is not just possible, but expected. It is often enjoyable; and in adult forms it can be extraordinarily effective.

Mythic language

Metaphor is the verbal equivalent of dual vision. “Bond market watchers are nervously eyeing the oncoming hailstorm of sovereign defaults.” Entirely unremarkable, likely passed over without notice—until you see this financial newspaper cliche as mythic vision. If you reread it and allow the mental image it evokes to gather vividness and detail, it becomes increasingly bizarre, uncanny and humorous.

Metaphorically speaking, mythic language paints pictures in our heads. Stories evoke more complex, moving images than individual metaphors.

From stories, we learn patterns of interpersonal interaction. The bond market may be distant from anything you care about. The story of how Aphrodite and Persephone both fell in lust with Adonis, and fought over him, but settled by splitting his year evenly between the two of them, is an archetypical human drama everyone can feel the force of, and reflect on.

From stories, we learn how the rhythms of rising and falling emotions go. “We dream in narrative, daydream in narrative, remember, anticipate, hope, despair, believe, doubt, plan, revise, criticize, construct, gossip, learn, hate and live by narrative.”2 Actions and events are meaningful mainly only for their place in a narrative.3

Mythic language also often relies on literal rhythm and rhyme. Mythic insight can often only be expressed in poetry. It’s still better to sing them. In every culture, before written language, bards sang myths, dreams, visions, and epic tales into being. Poetry is also the language of ritual, and rituals are often stories enacted. We structure rituals, extended in time, with their own rhythms of repetition, with internal variations analogous to rhyme.

The world of as-if

Mythic seeing and doing behave somewhat as if we are entering another world. A world of as-if has its own rules, and we act according to them.4 It has its own logic for what may happen when we do, and of what entities we will find, and how they will act in response.

A world of as-if has a membrane, a boundary, that separates it from the mundane. But, almost always, we retain awareness that we have created that membrane ourselves. That is often through a declaration, a magic spell: “Let’s play ‘princesses in the castle’!” Or: “The magic circle is cast; the ritual begins!”

An as-if world is always temporary; we “return” to the actual world when the game, daydream, or ritual is over. And if, in an as-if world, it is all you see, then you are in the domain of hallucination or madness, not the mythic mode.5

A mythic domain is our creation. Entering and acting in the as-if depends on skills, just as acting in the actual world does. Children’s play is childish: minimally skilful. Sophisticated spiritual practice, or effective religious ritual, may demand years of full-time training.6

Because we retain dual vision, we can and do negotiate and play with what counts as inside and outside. Which elements of actuality do we choose not to see during the ritual? After it is over, which aspects of the “other world” follow us into everyday life?

We have some choice here; but the as-if has its own power, players, and logic, who also get a say. This is not supernatural magic; it’s true for all human creativity. Novelists complain that their characters do what they want, taking the story in quite different directions than the writer intended. Painters find unexpected people, objects, or acts appearing on the canvas, disturbing or delightful, demanding inclusion.

The mythic mode recognizes that “as if” does not mean “false.” That is an error of rationalism.

The mythic mode also recognizes that the world of as-if is not true. We do not concretize it as real. This is a key difference between the mythic and the metaphysical. Metaphysics takes imaginary entities and worlds as even more real than the actual world. This is also a rationalist delusion.

In an upcoming post, I’ll explain how the Ancient Greek philosophers were misled by the Law of the Excluded Middle. They transmuted myth, which they considered false, into metaphysics, which they tried to believe was true. Rationalists created metaphysics to serve the same vital functions as myth: ones that rationality requires but cannot provide. This was a catastrophic mistake. Metaphysics is a pale imitation of myth; an inadequate and misleading substitute.

The mythic as-if is a space of energetic potential, of inchoate forms coming into being, of swirling shape-shifting self-possibilities.

This is where we discover major life-meanings.

It is in the mythic mode that we perceive sacredness.

In the as-if, we learn what and who we are, beyond conventional social roles.

There we find our “big” purposes, the ones that guide us through years and decades.

These are the topics of upcoming posts!

Wittgenstein used the duck-rabbit illusion as an example in his seminal discussion of “seeing as” in Philosophical Investigations.

Barbara Hardy, quoted in Kieran Egan’s The Educated Mind.

But see Galen Strawson’s “We live beyond any tale that we happen to enact,” Harvard Review of Philosophy 18 (2012) pp. 73–90.

I’ve taken the term “as-if” from Seligman et al.‘s Ritual and Its Consequences: An Essay on the Limits of Sincerity, a major influence on my understanding of the mythic mode. I wrote about it here.

Dreams are usually an exception. Lucid dreams, in which we recognize we are dreaming, have exceptional power for the mythic mode, however!

Tanya Luhrmann’s How God Becomes Real: Kindling the Presence of Invisible Others provides an accessible introductory explanation of the methods adults use to engage with the as-if, and how we learn them. She provides engaging examples from many quite different religions, taken from her ethnographic fieldwork.

I'm down with this! Two points though:

Mythicallity can be an explicit mode, set off by as-if markers. But I think it's also a kind of pervasive thing, that is, we are always telling stories about ourselves in the course of mundane activity, and those stories have roots in myth, taken broadly. This is the opposite of Galen Strawson, call it "pervasive narrativity".

You actually say pretty much exactly this, so I'm not disagreeing with anything (hard to believe I know). So what is my point? Not sure, maybe that myth is present to us in two different ways – explicitly and implicitly – and I'd like to understand the relationship better. (Also reminded that this is sort of the meta-theme of Joyce's Ulysses).

Two: there is a dark side of myth that is evident in politics and war. Politics runs on mythicallity more than most human activity; and those myths often involve conflict, enmity, and violence. Nationalisms are weaponized myths. Fascism also runs on mythologies, but its really a human universal. Myths are weapons of war, perhaps the most important ones, the motivating forces.

The suppression of myth in modernity, its replacement with more rational or utilitarian values – everybody hates that, but perhaps those old stories were stuffed into a box for good reason, they are dangerous as hell. Of course, they don't stay suppressed – Pandora always opens the box. Speaking of myths.

Would love if you should analyze the Mythopoetic Men's Movement from this perspective; as a vanished gathering that I enjoyed in times past, would be interested how you sort out (to the best of your memory), when it hit the nail on the head or went astray.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mythopoetic_men%27s_movement

Related: Criticisms and laudations you might have for the generation of Joseph Campbell, Jean Houston, Michael Meade, Huston Smith, Thomas Moore, Marion Woodman, James Hillman, and Robert Bly.

Once again as a more abstract question:

You say: "Depth psychology, particularly the work of Carl Jung, dominates popular conceptual understanding of the mode. Although that’s valuable, it’s also distorting. Thinking and feeling are aspects of all the modes, but so are perception and action—and they are at least as important."

In so far as some neo-Jungians DO emphasize perception and action...would love to hear more precise critique.