This post features a draft of a piece of my meta-rationality book. It is the first half of the second chapter of Part Four of the book. (Got that?)

The first chapter was an introduction to Part Four; you can read it here.

This second chapter is an overview of meta-rational practice. It has six sections:

When to get meta-rational

Meta-rational norms

Meta-rational processes, operations, and methods

Opportunities for meta-rational improvement

Meta-rational maxims

Fluid competence

This post includes the first three sections. I’ll publish the second three as a separate post, so they’re each about the right length for a newsletter issue.

(Right? Or is this too long? Or would you rather have had the whole chapter at once?)

My thanks to the nine readers who signed on as paying subscribers after reading my last post! I really appreciate it. This one is part-paid: there’s a paywall about halfway through.

Since it’s an overview, this chapter may be frustratingly abstract. I’m thinking of adding a concrete case study to it. Today I’m excited about the history of the discovery of penicillin, and will use that if I can make it do the work of illustrating major themes of this chapter.

I got taught a version of the story in high school biology class, and had never thought to question it until three days ago, when I discovered that it is completely false! And it’s not just completely false, it’s motivatedly false, in suggesting a model of scientific discovery that’s attractive but importantly and deliberately misleading! And the real story is much more interesting, although unattractive unless you actually care how science works!

As you can see, I get riled up about things like that, which is the main reason I write :)

This draft is “beta 1” quality, in software version jargon. “Beta” means I think it’s good enough to show the public, whereas earlier (“alpha”) versions have gone to only a handful of highly motivated readers. “1” means it’s the first beta version. It may be unclear, missing necessary explanations, or include factual errors. If you notice any of those, please leave a comment!

Meta-rational practice: an overview

There is no technical manual for meta-rationality, and there can’t be one.

This may disappoint. You already know how to learn technical skills quickly. If the power of meta-rationality attracts, you may hope to enjoy mastering it, easily enough, as a collection of well-defined techniques. However, meta-rationality works with nebulosity—indefiniteness—for which definite methods are inadequate.

If a definite method will do the job, you are in the realm of rationality, not meta-rationality. And that’s good! Rationality is great! So long as it works… which is as long as you can get away with ignoring nebulosity.

Meta-rationality is not the same sort of thing as rationality; it is not an alternative method for doing the same things. It’s a different way of being, for doing different sorts of things in a quite different way.

In particular, it is not a different way of Solving well-defined Problems. (The capital letters here indicate formal objects, as opposed to real-life situations.) Meta-rationality comes especially into its own in situations where rational methods get brittle and break, because the world refuses to conform to the given ontology. Meta-rationality is useful in setting up Problems; and it includes and uses rationality when appropriate. Setting up Problems well can make them easier to Solve.

You inherently can’t do meta-rationality “by the book”; it’s necessarily an open-ended inquiry. “What does the situation need?” may have answers of unenumerably different sorts. However, meta-rationality isn’t defective because it has no definite methods. That’s just an inescapable, neutral fact you need to get comfortable with.

Nevertheless, there is much to say—hundreds of pages of “how to.” While there are no crisp, general-purpose, reliably-applicable methods, there are a great many nebulous-but-describable intermediate-generality approaches that often work.

Those are the topic of this Part. Think of it not as a manual, but as a wilderness area guide, describing major landmarks and giving advice on equipment to take and wildlife to look out for.

This chapter is a preliminary overview of meta-rational practices and how we do them. Later chapters in this Part go into the same material in much greater detail.

When to get meta-rational

Any use of rationality involves meta-rational judgements—but usually only implicitly. Whenever you apply a particular rational method, you implicitly judge that it will prove adequate, and that it is the best available rational method to use in your current situation.

This choice is often made by applying a mindless default. You use the method that people like you use in situations like that, without considering alternatives.

So long as the method is reliably adequate in such situations, going with the default saves cognitive effort. However, no rational method can be entirely reliable, because nebulosity is pervasive. Using an unthought default—“oblivious rationalism”—always takes on some risk of failure. Whether that risk is worth taking is also a matter of meta-rational judgement; one that is also usually ignored and unthought.

Ideally, you should be meta-rational all the time. Any time you use rationality, you should be wondering “is there a better way of applying rationality here, taking into account context and purposes?”

When initially learning meta-rationality, this might take difficult, explicit thinking, which can delay or obstruct the rational work. However, with experience, it can fade into “background mode” most of the time. You need only retain a back-of-the-mind awareness, looking out for signs of trouble that may predict a rationality failure, and indications of opportunities for improvement in rational processes that are going well enough already.

How much reasonable vs. rational vs. meta-rational thinking to do depends on the specifics of the task and how it is going. Recognizing when and how to use each mode of reasoning is a key meta-rational skill. You gain a “feeling for the texture” of points at which explicit meta-rational reasoning may prove valuable.

Some roles require meta-rationality to a much greater degree than others. You may never need it as a technical individual contributor, if Problems are supplied to you already formalized, and if it’s well-known within your specialization what rational methods to apply to what sorts of Problems. Meta-rationality becomes increasingly important if your role includes responsibility for the functioning of a system that interfaces with nebulous aspects of external reality.

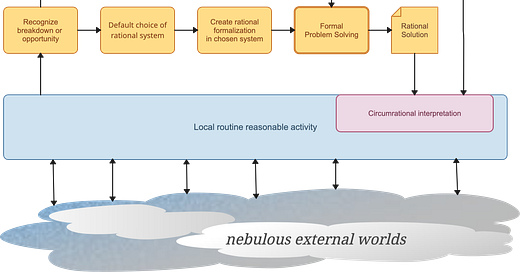

Meta-rationality is most obviously useful when rationality fails. There’s a striking parallel: rationality is most obviously useful when reasonableness breaks down. Reasonableness works only in “typical” situations. When it runs into stubborn trouble, and reasonable repair attempts fail, you either abandon the project underway, or recognize the situation as “atypical,” and step back and analyze the problem rationally. (We discussed this in the “Trouble” section of “Reasonableness is routine" in Part Two.)

Analogously, when rationality fails, you may attempt rational repairs. A software development project is months behind schedule, the codebase is a giant ball of spaghetti, the plan has disintegrated, the team is discouraged. As the project overseer, you can attempt rational repairs such as adding headcount, replanning, or assigning new leadership. Those may work! Or not. If not, meta-rationality may rescue the project—or not.

We’ll call situations in which rationality fails “anomalous”—in contrast with “typical” and “atypical.” Anomalous situations are ones that can’t be understood rationally. The software development plan was completely rational; it was replete with careful, empirically-based Excel-based cost estimates, personnel org charts, project GANTT charts, and system modularity diagrams. Reality started diverging from the plan almost immediately, for reasons no one could pinpoint. Eighteen months later, you’ve got an enormous incomprehensible mess. What happened? Rationally, everything should have worked! These are the kinds of situations in which meta-rationality may save the day.

Just as rationality can sometimes improve reasonable activity that is going well-enough, meta-rationality can also sometimes improve rational activity that is going well-enough. Let’s say you are a microeconomics researcher doing field work in a large “knowledge work” company, in finance or technology for example. After months embedded in the corporation, and talking to hundreds of employees, you are puzzled. About eighty percent of them do things that produce no economic value. Some perform circumrational tasks that could be automated easily, but aren’t. (Circumrational activities are those that interface a rational system with its surrounds, such as data entry.) Others perform elaborate rationality theater, writing reports and building spreadsheets that are never used. Everyone accepts this as perfectly normal, and the company is profitable and growing. To the participants, rationality seems to be working just fine.

But not to you. It looks highly irrational. Basic microeconomic theory says upper management must be compelled by market forces to eliminate those jobs. If they don’t, a competitor will, and will be able to radically cut prices, which will put this company out of business. But that doesn’t happen. This is an anomalous situation. It cannot be understood from within the rationality of microeconomics.

Whether a situation counts as anomalous depends on the system from within which you view it. Meta-rationality may recommend considering applying alternative rational systems. For example, the “anomaly” might make perfect sense when viewed from within industrial sociology or organizational psychology. With an alternative understanding, you may see ways to improve the situation, perhaps by making the unproductive work valuable, or recognizing that it is already valuable in a way microeconomics overlooks, or by the changing the executive incentives that maximize headcount at the expense of efficiency.

An exercise for practice

To make this concrete: think of times when you considered what rational system to apply in a situation, or how to apply it, or whether formal rationality would be useful at all. If you can remember such—you were doing meta-rationality then!

Can you think of times when a project you were working on, or are familiar with, ran into an anomaly that resisted rational repair? What happened then?

Can you think of times when you, or someone else working with you, brought an alternative system to bear on a project? How did that work out?

Meta-rational norms

We saw in Part Three that accepting the nature of rational norms is a major initial obstacle to gaining rational competence. This is emotionally as well as cognitively difficult, and can precipitate extensive psychological reorganization.

The same is true for meta-rationality: the nature of the norms initially seems unacceptable if you hold rational ones. Understanding what that nature is, and why these norms are necessary, is a big first step into meta-rational competence. This too can be emotionally as well as cognitively difficult, and can precipitate extensive psychological reorganization.

We can summarize the distinctive norms of reasonableness, rationality, and meta-rationality, together with the nature of norm violation versus conformity in each:

Reasonableness: recursive, groundless accountability in concrete, improvised activity; subject to unbounded interpretation and negotiation that terminates in reasonable judgement in practice.

Rationality: adherence to principled formal rules; at least in theory, everything you do is either absolutely correct or absolutely wrong.

Meta-rationality: ongoing panoramic responsiveness to purposes, context, and situational specifics; norm violation manifests as oblivious geekery, and success as “intuitive” “creative” “magic,” inexplicable in rationalist terms.

Let’s recap the norms of reasonableness and rationality in greater detail, together with examples; and then contrast the norm of meta-rationality.

The fundamental norm of reasonableness is that you must be able to provide a reasonable account of your activity, which orients to unenumerable specific, commonsense concrete practical and social considerations that are obvious in the situation.

Example: “I’m late to work because of the bus drivers’ strike.” This orients implicitly to the social norm of getting to work on time; the practical trouble caused by failure of your routine of catching the 7:10 bus; and the reasonable consideration that this could not be repaired by catching the next bus, and therefore constituted a breakdown, which (you are claiming implicitly) gets you off the hook by way of the social norm that breakdowns caused by third parties are not your fault.

This fundamental norm is endlessly negotiable, in principle; nothing is absolutely correct or incorrect as a reasonable account.

The fundamental norm of rationality is that a Solution must formally match the requirements of the Problem; ideally, the Solution is derived through absolute adherence to formal rules, which are also the terms in which the Problem was stated.

Example. Problem: determine whether reaction A or B dominates when molecules C and D are mixed. Solution: “Iterative quantum molecular orbital calculations using a Hartree-Fock model demonstrate that reaction A is energetically preferred to reaction B by 5.8 kcal/mol.” This Solution orients to a general, abstract, formal theory (the Hartree-Fock model of molecular orbitals) and to a general, abstract, formal method (iterative numerical approximation).

A rational Solution may also orient to situational specifics (“true facts”). In the case of administrative and legal rationality, it may orient to social norms as well, although those will be stated in relatively formal natural-language terms, subject to special rules of inference, that laypeople could not accurately interpret.

The fundamental norm of rationality is (in the ideal) perfectly inflexible and impersonal and absolute; either a proposed Solution is correct, or it is not, regardless of purposes and context.

The fundamental norm of meta-rationality is to consider specifics in the light of as many considerations of broad context and purpose as seem relevant and are feasible to incorporate, and to bring elements of rationality to bear only if, when, and to the extent that their conditions for adequacy hold, and only in ways that will plausibly prove useful. In other words: “What does the situation need?”

Meta-rational judgement is required in deciding “if, when, to what extent, and in what ways” rationality is called for; and what to do if it’s not. Such judgement orients to concrete specifics and social norms (as in reasonableness), and to abstract theories and formal methods (as in rationality), and to meta-rational maxims. (Meta-rational judgement and meta-rational maxims are the subjects of two upcoming sections.)

Example. “This tidy epidemiological model of the novel pathogen omits consideration of the emerging religious opposition to the (admittedly horrifying) countermeasures. We can’t make a meaningful quantitative model for how strong that opposition will grow over time. That means we can’t make the kinds of predictions we built the tidy model for. Can we adapt it into a qualitative model that would useful guidance for action anyway?”

This orients to concrete specifics (the horrific nature of the countermeasures), to social norms (religious opposition), to rational theories and methods (epidemiological models and quantitative predictions derived from them), and to a meta-rational maxim: “It’s common when building rational models to simply ignore factors that are too nebulous to fit the formalism; and eventually they usually bite you in the rear.”

Here, violating the norm is the oblivious geekery that left out social opposition because it was impossible to model quantitatively. That could result in unboundedly inaccurate predictions.

Meta-rational practices

We can expand the compact definition of the meta-rational norm into a collection of practices. These are still quite abstract; we’ll consider them in more detail as Part Four goes along. Here are a dozen meta-rational practices, derived from the norm: